Pentremites, a common Missisiippian Blastoid, image

shown

with permission from

the University of California Museum of Paleontology

Invertebrate Paleontology Lab #11

Phylum

Echinodermata

Click on the lab title to see the University of

California

Museum of Paleontology web page

Read BEFORE Coming to Lab: Benton & Harper, p. 389-409

Introduction

This week we will explore the very diverse and

successful

Echinoderm

Phylum. The five living classes of echinoderms today include

the sea stars, brittle stars, sea urchins, crinoids and sea cucumbers,

but abundant as these are, they represent just a remnant of an immense

group that once included 20 different classes. The organisms are

perhaps best known for their water vascular system, which

operates

the tube feet as well as governs gas exchange and feeding

processes.

Echinderms also have an endoskeleton, composed of many little

plates

that can articulated or fused together. These plates are called ossicles,

and are embedded in the dermal tissue. The endoskeleton assures a

good chance for fossilization, because it is these ossicles that are

often

preserved in the fossil record.

Echinoderms have a remarkable feature that is

unique

in the animal kingdom: they can reverse the rigidity of their

dermal

cells and connective tissue. This is most evident, for example,

in

the action of a starfish as it attacks a pelecypod. The

connective

tissue stiffens, and provides a framework against which the tube feet

can

pull as the pelecypod's valves are forced open. Later, the

starfish

can soften the connective tissue, return to its flexible condition, and

move away. Apparently, the ability to reversibly affect the

rigidity

of the dermal and connective tissue is directly related to controlling

the concentration of calcium ions in the tissues. To read more

about

this interesting feature, I recommend Ruppert et al. (2004) (reference

is below).

Basic Facts to Know about

Echinoderms: They are |

|

| 1. |

Eukaryotes |

| 2. |

Metazoans with organs, true tissues, nervous, muscular,

and reproductive

systems |

| 3. |

characterized by an endoskeleton composed of ossicles

(calcite plates) that can be articulated or fused |

| 4. |

characterized by unique ability in the Animal

Kingdom to reverse

the rigidity of their connective tissue |

| 5. |

characterized by radial symmetry, often visible as pentameral

(5-rayed) in some groups |

| 6. |

characterized by an internal water vascular system that

operates

movement, feeding, gas exchange |

| 7. |

limited to marine environments only because of lack

of osmotic

regulation |

| 8. |

Excellent index fossils: widely distributed,

well preserved,

easily identified, rapidly evolving |

| 9. |

found to filter feed, or to be heribivores, predators,

scavengers,

and detritivores |

| 10. |

gonochoric (males and females present, with a few

exceptions)

and larvae have a planktonic phase |

Crinoids, Blastoids, and other Stalked Echinoderms

Class Crinoidea (Cambrian to Recent)

The Crinoids represent the only living group of

stalked echinoderms still in existance. They have a fossil

history

that extends into the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale. The crinoid

body consists of a calyx or theca, which houses the internal

organs

and bears the arms which are used for feeding. Attached to the

theca

is a stalk or column that consist of disks of calcite

columnals,

pierced through the center by a fibrous mass of collagen. The

stalk

is anchored to the substrate with a holdfast, which looks very

similar

to plant roots. Upon death, the collagen breaks down and the

columnals

are released like beads from a broken necklace. If wave energy is

slight, the column is likely to stay more or less intact, however, any

wave action or current action will scatter the columnals, and often in

the fossil record, a columnal hash deposit results. Like all

echinoderms,

they have endoskeletal ossicles, and a water vascular system that

operates

the feeding arms. The arms have ambulacral food grooves

that

move food towards the mouth, which is in the center of the calyx

(theca).

The arms extend into the water current, trap food particles which move

via mucus along the ambulacral grooves to the mouth. The gut is a

simple loop that terminates in the anus, which is next to the mouth on

the top of the calyx. The arms were strong, containing extensions

of the coelem, and are often preserved.

Figures of Crinoid Terminology and fossil Crinoid shown with permission

from the University of California Museum of Paleontology

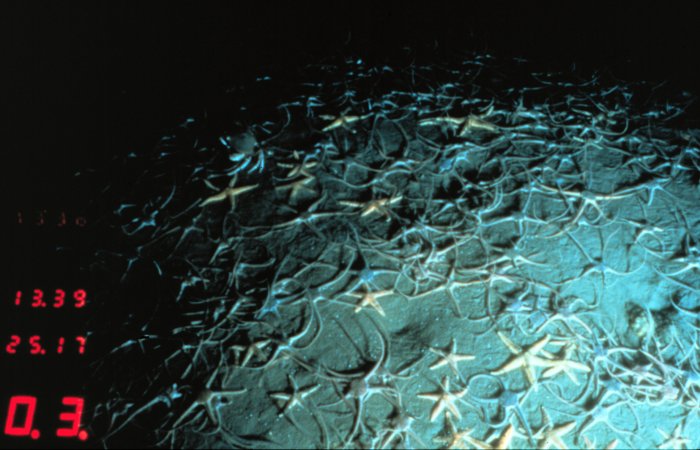

Class Blastoidea (Middle Ordovician-Late Permian)

The Blastoids are the second most common group of

stalked echinoderms. The calyx of blastoids shows a strong

pentameral symmetry, and looks like a nut or the bud of a flower.

The arms were very delicate, with no coelemate extension, and are not

usually

preserved. The mouth is a simple opening located in the center of

the top of the calyx, and surrounded by typically five circular

openings

called spiricles that apparently served as the exhalent currents.

These openings can be clearly seen in the photo below, where the center

view shows the star-shaped opening that is the mouth, and the

surrounding

spiricles. The largest of the spiricles is the anal opening (the

anispiricle). In side view of the calyx, you can see the

ambulacra,

where the arms (brachioles) would have attached.

Calyx View of Pentremites, a common Blastoid of the Mississippian,

shown with permission from

the University of California Museum of Paleontology

Part I, 20 pts. : Examine the Blastoids and

Crinoids in the Teaching

Collection, and

draw two of these, labelling the calyx, the spiricles (if visible), the

ambulcra, and the columnals (if present). Label the top (oral

side)

and the bottom (aboral side) of the calyx. Label the class and

time

range, as well.

Examine the teaching

collection and pick two non-stalked

echinoderms.

Draw them, labelling the madrepore, the ambulacral area, and the

mouth.

Label the Class and time range, as well.

|

Brittle Stars, Starfish, Edrioasteroids

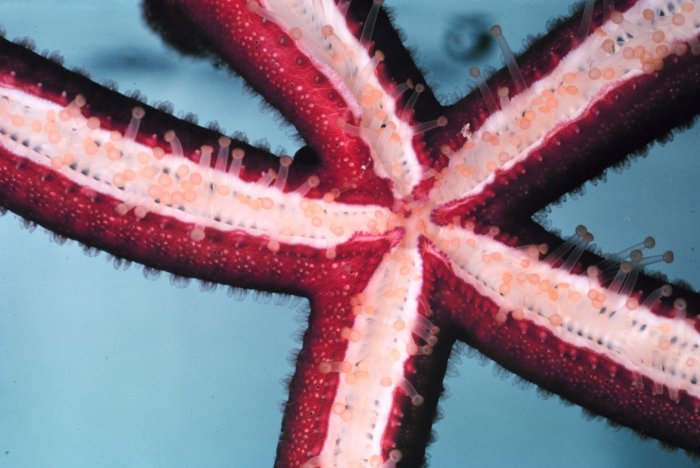

Class Asteroidea (Early Ordovician-Recent) (Starfish)

The "starfish" appears a early as the Ordovician, and became an

important

predator through the Phanerozoic. They are not typically well

preserved,

because the ossicles are very tiny and not articulated together.

Often star fish have five arms, with the tube feet running along the

ambulacral

arms. The mouth is located on the underside of the starfish, and

the anus and madreporite (the main water entry control for the

water

vascular system) is located on the top. The starfish are able to

evert their stomachs and digest their victim within its own

shell.

There is quite a bit of discussion in the literature concerning the

role

starfish played in the development of complex hinges and commisures in

the mollusks, in the collapse of the brachiopods in the Mesozoic, and

their

role as prolific predators in the Mesozoic marine revolution.

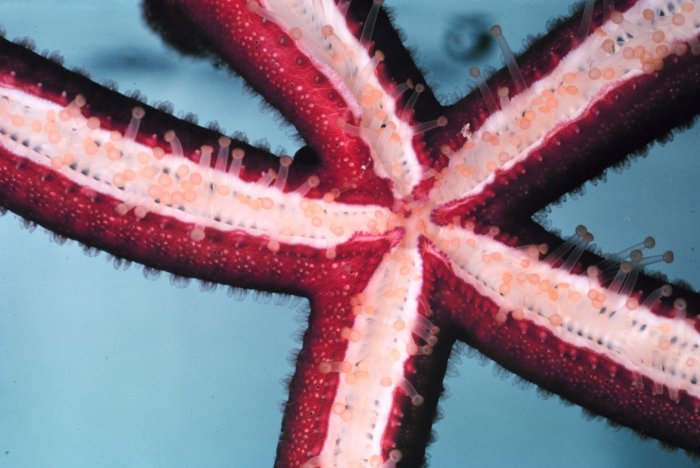

Image of fossil starfish shown with permission from the University

of California Museum of Paleontology, live starfish showing underside

with

tube feet visible, shown courtesy of NOAA NURP, Image ID: reef0206, The

Coral Kingdom Collection Credit: Photo Collection of Dr. James P.

McVey,

NOAA Sea Grant Program

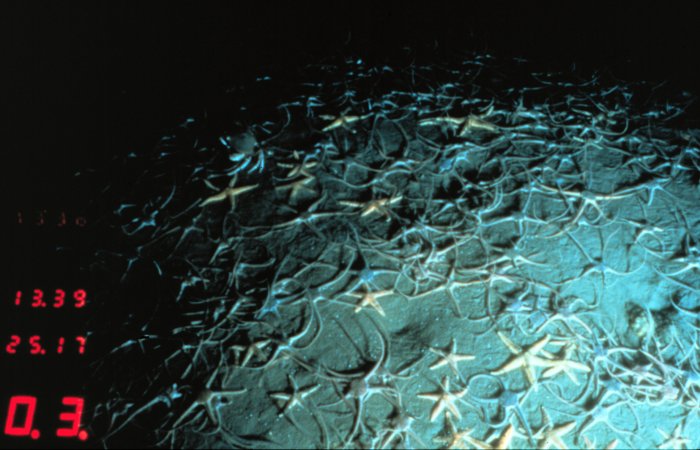

Class Ophiuroidea (Early Ordovician - Recent) (Brittlestars)

Similar to starfish, ophiuroids (brittlestars) typically have five

arms, but these tend to be very thin arms, radiating from a central

disk.

The mouth is located on the underside of the disk-body, and the anus

and

madreporite on the top. However, there is no coelomate extension

through the arms, as in the starfish, and so the primary use of the

arms

is in wriggling about to provide locomotion for the brittlestar.

They are a major component of the deep ocean floor benthos-very few

species

live in shallow waters today.

Image of fossil brittlestar shown with permission from the University

of California Museum of Paleontology, image of live brittlestars on the

floor of the deep ocean shown courtesy of NOAA NURP.Image ID: nur01504,

Photographer: S. Stancyk Credit: OAR/National Undersea Research

Program

(NURP); University of South Carolina

Class Edrioasteroidea (Early Cambrian-Late Pennsylvanian)

This interesting group consisted of small (about 1 cm diameter)

circular

shaped animals that attached to hard surfaces. On the top surface

is an arrangement of five loosely coiled or curving ambulacral

arms.

The tube feet caught food particles and transported them to the

mouth.

They are fairly common in the Cincinattian limestones of the

Ordovician,

so you may have collected some in your own samples. They are

often

found cemented onto brachiopods, particularly strophomenid brachiopod

valves.

Image of fossil Edrioasteroid shown with permission from the University

of California Museum of Paleontology

Sea Urchins, Sand Dollars, Sea Biscuits, Heart

Urchins

Class Echinoidea (Late Ordovician-Recent)

As a group, echinoids tend to be found as fossils more commonly than

the other echinoderms. This is because the ossicles are fused

together

to make a strong structure that is often preserved in the burrows in

which

the animal lived. The mouth is on the underside, the anus is

located

on the top, near the madreporite plate, and there are typically five

ambulacral

grooves where the tube feet are located. The tube feet vary

considerably.

The tube feet on the bottom are designed for locomotion, whereas those

on the top are for respiration, and there are also long stalks with

grasping

claws called pedicellaria that remove debris and protect the echinoid

from

smaller organisms. All echinoids possess spines, which

are

composed of single crystalline masses of calcite. The spines can

pivot at the base, and thus move in different orientations. There

are two major groups to consider:

The Regular Echinoids (Late Ordovician-Recent)

This group includes the the sea urchins, which have

a radial symmetry, feed on algae by scraping it off rocks with a

feeding

structure called Aristotle's lantern, and have a fossil record

that

extends back to the Ordovician.

Regular Echinoid sea urchin, photo courtesy of NOAA NURP Credit: Photo

Collection of Dr. James P. McVey, NOAA Sea Grant Program

The Irregular Echinoids (Jurassic - Recent)

This group includes the sand dollars, sea biscuits,

and heart urchins. The irregular echinoids are marked by a

secondary

bilateral symmetry, as the whole body is flattened, and consequently

the

anus moved towards the posterior of the shell, and the mouth stayed

central

or moved towards the anterior. Most irregular echinoids burrow,

and

thus have limited ambulacral areas (just on the top of the

shell).

Food grooves with tube feet move food particles along on the underside

of the shell towards the mouth. An extreme body design of

this

group is the flat sand dollar, which first appeared in the early

Tertiary,

and which has slits or lunules in the shell to prevent it from

being

lifted out of the sediment by wave action while it is feeding.

Sand Dollar Image shown with permission from the University of

California

Museum of Paleontology

For More Information...

For more on the fascinating biology of this group, I recommend

Ruppert, Fox and Barnes, 2004 Invertebrate Zoology, , 7th edition,

Chapter 28, Echinodermata, pp. 872-929.