Coastal Pollution Policy Issues

The many facets of marine pollution require a multi-faceted approach to solutions. New approaches include:

i. Enhance Cooperation Among Federal, State,

and Local Governments

The coastal zone is managed by many different governmental agencies,

yet the waste and pollutants know no political boundaries. Good management

requires agencies to work together. This can lead to better working relationships

and to rules and regulations that extend across political divisions.

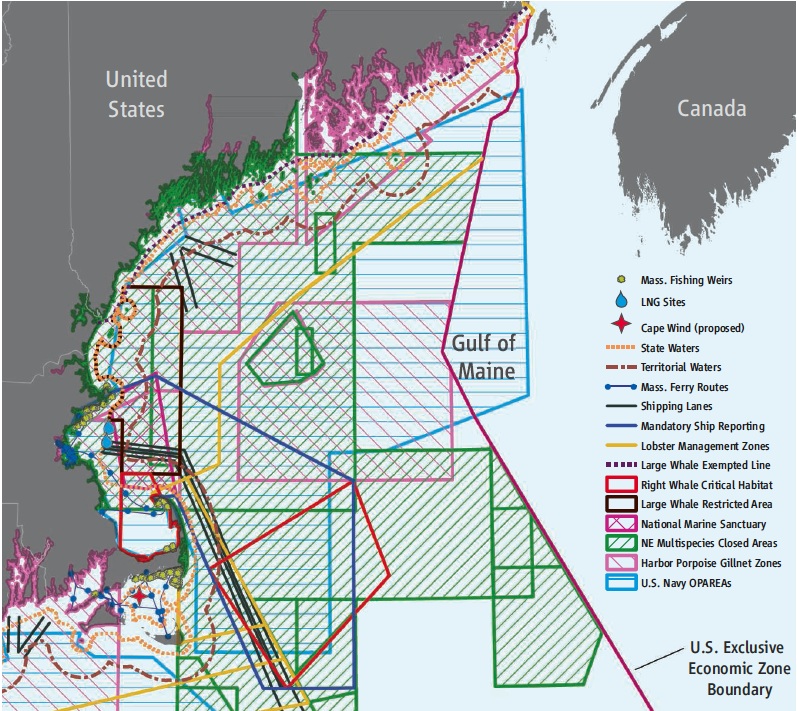

Maps still depict the vibrant seas in featureless monotones with simple borderlines drawn three, twelve, or two hundred miles offshore. Such limits are grossly misleading. They overlook the impact of land-based activities on the marine environment and miss the complexity of ecosystems. A time has come for better governance, incorporating an awareness of ecological dynamics in decision making about marine resources ... The domestic three-mile limit that divides state from federal authority [in the U.S.] was never based on enlightened ecological thinking, but was a mere consequence of muddling through. Yet it persists today. What began as a novel eighteenth century neutrality zone for warships is much harder to justify as a basis for ocean management.

From Wilder (1998) Listening to the Sea.

Activities in the Gulf on Maine are regulated by many different state and federal agencies. The regulations are not consistent with ecosystems based management of marine resources.

From Turnipseed et al (2009).

2. Reduce Pollution From Non-Point Sources

We've done a good job tackling many of the obvious causes of ocean pollution--ocean dumping, discharges from industrial facilities, and toxic pollutants," said Leon Panetta, chair of the Pew Oceans Commission. "Now we need to get serious about the less obvious sources of pollution that flow from our cities, farms, and ships if we want to protect our coastal waters and the communities they support.

From Pew Charitable Trusts report on Protecting Ocean Life.

3. Manage Watersheds and Ecosystems Not Bays

and Estuaries

This approach has been applied to the Chesapeake Bay

andit is the basis of the traditional ahupua'a divisions of land in

Hawai'i.

We must encourage all citizens of the Chesapeake Bay watershed to work toward a shared vision — a system with abundant, diverse populations of living resources, fed by healthy streams and rivers, sustaining strong local and regional economies, and our unique quality of life.

The Chesapeake Bay’s natural infrastructure is an intricate system of terrestrial and aquatic habitats, linked to the landscapes and the environmental quality of the watershed. It is composed of the thousands of miles of river and stream habitat that interconnect the land, water, living resources and human communities of the Bay watershed. These vital habitats–including open water, underwater grasses, marshes, wetlands, streams and forests–support living resource abundance by providing key food and habitat for a variety of species. Submerged aquatic vegetation reduces shoreline erosion while forests and wetlands protect water quality by naturally processing the pollutants before they enter the water. Long-term protection of this natural infrastructure is essential.

In managing the Bay ecosystem as a whole, we recognize the need to focus on the individuality of each river, stream and creek, and to secure their protection in concert with the communities and individuals that reside within these small watersheds. We also recognize that we must continue to refine and share information regarding the importance of these vital habitats to the Bay’s fish, shellfish and waterfowl. Our efforts to preserve the integrity of this natural infrastructure will protect the Bay’s waters and living resources and will ensure the viability of human economies and communities that are dependent upon those resources for sustenance, reverence and posterity.

From CHESAPEAKE 2000 Agreement. More information is at the Chesapeake 2000 web site.

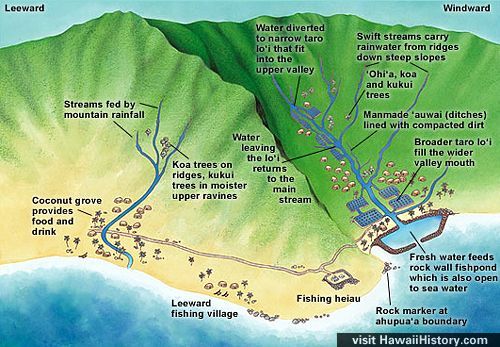

The native Hawai'ian islanders developed over many centuries a very effective method for managing their environment. Their very survival depended on their ability to manage their forests, cropland, and fisheries. They divided their land into ahupua'a:

These divisions (ahupua'a) radiated from the interior uplands, down through deep valleys, and past the shoreline into the sea. They became the basic unit of the Hawaiian socio-economic organization (see illustration). This type of land division allowed exploitation of all the resource zones of the island — forests, agricultural land, shoreline, and ocean — by a single socio-political group and guaranteed them some degree of self-sufficiency and economic independence.

All of the resources within this strip were restricted to use by its inhabitants. The name derives from ahu, an altar erected at the intersection of the land division boundary with the main road around the island, and pua'a, a pig, represented by a carved wooden image of a hog's head placed on the altar. Because a pig was an acceptable tribute, it represented any tribute-in-kind. Residents deposited gifts at this site each year during the annual harvest festival (Makahiki). The size of the ahupua'a varied, the larger ones on the island of Hawai'i being located in the interior.

Rights to irrigation water and fishing areas, considered very valuable economic assets, were strictly controlled within an ahupua'a. Water rights were codified to assure the equitable distribution of free-flowing waters for irrigation. Inshore fishing rights were explicitly stated. Normally only members of an 'ohana had rights to exploit specific water areas of the 'ohana lands. These rights usually included the inshore waters out as far as a man could stand upright with his head above water. A chief or konohiki, however, could place kapu on the use of certain types of fish and other marine resources at certain times or by certain people.

From A Cultural History of Three Traditional Hawaiian Sites on the West Coast of Hawai'i Island: Chapter 1.

A sketch of an Ahupua`a on an Hawai'ian island.

From Honolulu Board of Water Safety and HawaiiHistory.

Hawai'i is now returning to these ancient traditions.

The Hawai‘i Coastal Zone Management Program (CZM Hawai‘i) is currently engaging the Wai‘anae community and other partners to develop a management framework that applies ahupua‘a (a traditional land division) values and practices. The Wai‘anae moku, or traditional land district, is composed of nine ahupua‘a, each unique and facing different environmental challenges.

From Wai'anae Ecological Characterization.Modern ahupua‘a management focuses on fostering stewardship of the land and sea and understanding of the interconnectedness of the health of our environment and ourselves. It provides opportunities to promote community-based efforts with localized knowledge to take an active part in decisions about the use of the ahupua‘a. Partnerships and the active involvement of stakeholders are essential for integrating ahupua‘a principles and practices within a modern government organizational and legal framework.

From Wai'anae Ecological Characterization: Ahupua'a Management and the WEC.

4. Decentralize Authority Toward

Local Levels Closest to the Problem

Local people know the problems, and they are better able to find solutions

what work best in their area. The coastal problems in Texas differ in many

ways from those in California or Alaska, and they have different solutions.

Many areas not employ a BayKeeper,

a full-time, local person who is a public advocate for that body of water,

and who works with all users of a coastal area. The Galveston

Bay Conservation and Preservation Association has hired a BayKeeper

for their area, Mobile

Bay, San Diego, and the New York Hudson/Raritan

Estuary are some other prominant bays or estuaries with BayKeepers.

5. Restore Coastal Ecosystems So They Are Better Able to Resist Pollution

Temperate estuaries worldwide are undergoing profound changes in oceanography and ecology due to human exploitation and pollution, rendering them the most degraded of marine ecosystems. The litany of changes includes increased sedimentation and turbidity; enhanced episodes of hypoxia or anoxia; loss of sea grasses and dominant suspension feeders, with a general loss of oyster reef habitat; shifts from ecosystems once dominated by benthic primary production to those dominated by planktonic primary production; eutrophication and enhanced microbial production; and higher frequency and duration of nuisance algal and toxic dinoflagellate blooms, outbreaks of jellyfish, and fish kills. Most explanations for these phenomena emphasize “bottom-up” increases in nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus as causes of phytoplankton blooms and eutrophication, an interpretation consistent with the role of estuaries as the focal point and sewer for many land-based, human activities. Nevertheless, long-term records demonstrate that reduced “top-down” control resulting from losses in benthic suspension feeders predated eutrophication.

Vast oyster reefs were once prominent structures in Chesapeake Bay, where they may have filtered the equivalent of the entire water column every 3 days ... Only then, after the oyster fishery had collapsed, did hypoxia, anoxia, and other symptoms of eutrophication begin to occur in the 1930s, and outbreaks of oyster parasites became prevalent only in the 1950s. Thus, fishing explains the bulk of the decline, whereas decline in water quality and disease were secondary factors.

From Jackson (2002) Historical Overfishing and the Recent Collapse of Coastal Ecosystems.

If the oyster beds were restored, and sedimentation of the bay were reduced so sea grasses could once again flourish, the influence of pollution would be much reduced.

6. Put Caps on Local Development

Some bays, estuaries, and coastal wetlands

need to be undeveloped reserves.

7. Restore Damaged Wetlands

NOAA's Damage

Assessment and Restoration Program is the primary office for restoration

in the U.S.

- Damage from each spill is evaluated.

- Cost of restoration is determined.

- Person of corporation causing the damage is fined.

- The fine is used to pay for restoration.

- Case Study: The Mobile

Gypsum Restoration Project, Houston Ship Channel,

Texas.

- Event. On April 6, 1992, a 600-foot long section of retaining wall of a gypsum slurry pile failed at the Mobil Mining and Minerals facility in Pasadena, Texas, causing 45 million gallons of a 3 percent phosphoric acid and hydrated gypsum mixture to spill through a small bayou and into the Houston Ship Channel. The spilled material had a Ph of 1.5.

- Damage. The spill caused significant injuries to freshwater, marine, and estuarine wildlife, fishes, invertebrates, plants and sediments. There was a significant loss of habitat for terrestrial and aquatic animals in the upland fields and drainage canals. There was also direct mortality to terrestrial animals, primarily ground-nesting birds, rodents, and reptiles. The injury to the surface waters was widespread. This adversely affected the water quality within approximately 7 miles of the Houston Ship Channel for at least one week.

- Fines. Mobil Mining and Minerals undertook response actions to contain, neutralize and remove contaminated water and soil and agreed to a compensatory restoration project. They agreed to pay pay $130,102 in fines, to undertake and pay for a wetlands restoration project covering an area of 32 acres of intertidal estuarine marsh and enhanced uplands habitat, and to pay $100,000 for maintenance of the project for three years after completion.

- Restoration Work. The trustees created a high-quality tidal wetland that includes brackish water finfish nursery habitat. Seventeen acres of sloping upland areas were lowered to create diverse shelf levels with increased water circulation. Inlets to the ship channel were created for improved circulation and access for fish. The trustees also enhanced a 15-acre freshwater wetland by removing nutrients and improving water quality. The watercourse between the ponds and the shallow wetlands now meanders, increasing the total time that plant outfall water remains in the system. Additional site-adapted plants enhance water retention and upland habitat values for birds and wildlife.

8. Establish National Marine Sanctuaries Where Human Influence Is Reduced, and Marine Life Can Flourish

To date, networks of fully protected marine reserves are the best-understood tool for managing marine ecosystems. Over the last 15 years, study of more than one hundred reserves shows that reserves usually augment population numbers and the individual size of over exploited species. Reserves provide protection from three major consequences of overfishing.

- They protect individual species of commercial or recreational importance from harvest inside reserve boundaries.

- They reduce habitat damage caused by fishing practices that alter biological structures, such as oyster reefs, necessary to maintain marine ecosystems.

- Reserves protect from ecosystem overfishing, in which removal of ecologically pivotal species throws an ecosystem out of balance and alters its diversity and productivity.

Within reserves, protection from all three types of overfishing is well known to spark ecosystem rebounds. Examples of these rebounds form a solid empirical backdrop for the use of reserves as a management tool.

From Pew Ocean Commissions Report on Marine Reserves: A Tool for Ecosystem Management and Conservation.

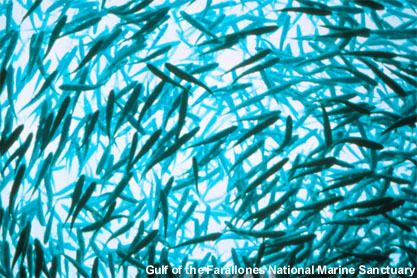

A swirling mass of jack mackerel Trachurus symmetricus forms a "bait ball" which draws feeding seabirds and marine mammals at the Gulf of Farallones National Marine Sanctuary.

From Gulf of Farallones National Marine Sanctuary

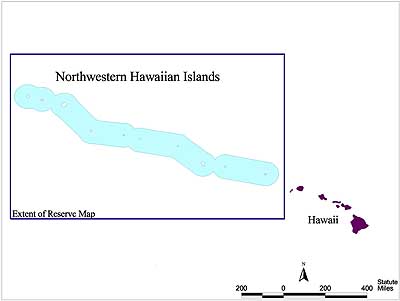

The largest in the United States is the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve.

Northwestern Hawaiian Islands National Marine Sanctuary.

From: Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve.

Unfortunately, most marine protected areas do not ban many harmful activities. For example, fishing is completely banned in only 14 of 220,000 square miles in the California Marine Protected Areas. (McArdle, 2002).

9. Simpler Lifestyles

I have lived in places like the Fiji Islands, where people subsisted on far less income and with far fewer material goods than I was used to as an American – yet people there were family-oriented, spiritually rich, and joyful.

From Wilder (1998) Listening to the Sea.

Reference

Jackson, J. B. C., M. X. Kirby, et al. (2001). "Historical Overfishing

and the Recent Collapse of Coastal Ecosystems." Science 293

(5530): 629–637.

McArdle, Deborah A. 2002 California Marine Protected Areas: Past and Present. California Sea Grant College Program, University of California, San Diego. 24 pp.

Turnipseed, M., L. B. Crowder, et al. (2009). OCEANS: Legal Bedrock for Rebuilding America's Ocean Ecosystems. Science 324 (5924): 183–184.

Wilder, R. J. (1998). Listening to the Sea: The Politics of Improving Environmental Protection. Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press.

Revised on: 29 May, 2017