Impressionism:

Iceland Fisherman

Iceland Fisherman (1886), Viaud's fifth novel, has yet a different relationship to the pictoral art of its time. Unlike the Near East and Tahiti, Brittany, the land setting of much of the work, was known to many of its potential readers. For reasons that I have dealt with elsewhere ("Different Contexts, Different Sexualities: A Gay Reading of Loti's PÍcheur d'Islande," Dalhousie French Studies 44 (Fall 1998): 65-80), Viaud had reasons for wanting to make the images in his novel less precise than they were likely to have been in the minds of readers who already had clear, often experience-based mental pictures of much of what he was describing.

To this end, Viaud turned to contemporary painting, and very specifically to the Impressionists, for techniques that would render the subjects of his writing imprecise. He sought verbal equivalents of Monet's painterly style to suggest, rather than describe, the settings in this text.

Nowhere is this more true than in his descriptions of the view from the fishing boats when at sea. Everything is "almost," "more or less," "probably," "perhaps," "it seemed," etc. In addition, the text focuses on things that cannot be depicted precisely. The following passage, typical of the style in this novel, comes from the first chapter:

But it was a pale light, pale, resembling nothing; it trailed across things like the reflections of a dead sun. Around them, an immense emptiness suddenly occurred, one that was of no color, and beyond the planks of their boat, everything seemed diaphanous, impalpable, chimeric.

The eye could barely grasp what must have been the sea: at first it took the appearance of a kind of trembling mirror that had no image to reflect; as it stretched out, it seemed to become a vapor plain, -- and then, there was nothing more: it had neither a horizon nor contours.

. . . . above, formless, colorless clouds seemed to contain a latent light that could not be explained. (Part I, Chapter 1).

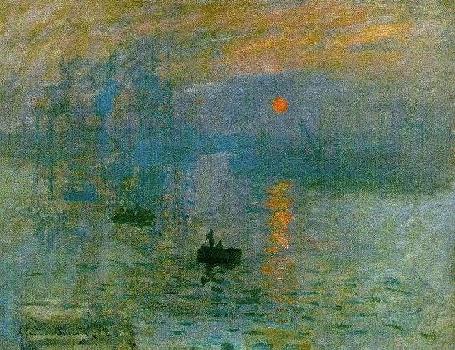

All this is extremely reminiscent of the style of Claude Monet (1840-1926). Monet's 1873 painting, "Impressions: soleil levant," first exhibited thirteen years before Iceland Fisherman, with its play of light, indefinite forms, and soft tints, a work that lead to the creation of the term "impressionism" to describe this type of painting, is a particularly striking painterly example of the effects that Viaud achieves through his own medium, language.

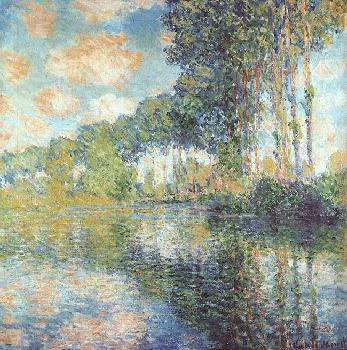

Other examples of Monet's use of light to create indefinite forms and colors:

As you can see, Viaud had a painterly contemporary who was busy doing with oils exactly what the novelist wanted to achieve with language.

Though much of Iceland Fisherman is set at sea, which made it particularly easy for Viaud to create a world of no definite colors or shapes, the author also managed to suggest such an atmosphere even when describing the scenes that took place ashore, in Brittany. When Gaud recalls her return to live in Brittany, the text remarks:

the train coming from Paris had deposited them, her father and herself, in Guingamp, on a misty and whitish, very cold early morning, still on the edge of darkness. . . . This quiet pace of life with people of another world going about their tiny little business in the fog! . . . They, her father and she, had traveled the whole afternoon of that same grey day . . . passing . . . under the ghosts of trees that sweated fog in fine little droplets. (Part I, Chapter 3)

Yet another Monet painting, "Poplars on the Epte" (1891), captures the uncertain image that Viaud suggests in his descriptions of Brittany, in particular the "ghosts of trees that sweated fog in fine little droplets."

The Paimpol dock . . . was full of people. . . . The ships were leaving two by two, four by four. . . . (Part V, Chapter 2)

Monet's 1874 painting of "Fishing Boats Leaving the Harbor, Le Havre" captures both the scene of and Gaud's mood at Yann's departure on the Léopoldine, near the end of the novel.

You could see sketched out, far in the distance, one after the next, all the breaks in the coastline, Brittany came to an end in notched points that stretched out over the tranquil nothingness of the waters. (Part V, Chapter 8)

"Coast of Portrieux," an 1874 painting by Eugène Boudin, one of Monet's

teachers, captures both the setting and the atmosphere of the Brittany coast

as Gaud sees it while waiting for the return of Yann and the Léopoldine.

Turn of the century American painters also developed a fascination with Brittany, though for them it was often because of what they saw as the Bretons' simple life, as opposed to the increasing complications of American industrialisation. Here are a few American glorifications of that Breton simplicity.

Walter Gay (1856-1937): Novembre, Etaples (about 1885)

(Source: Smithsonian website)

William Henry Lippincott (1849-1920) Farm Interior: Breton Children Feeding Rabbits (1878)

(Source: Smithsonian website)

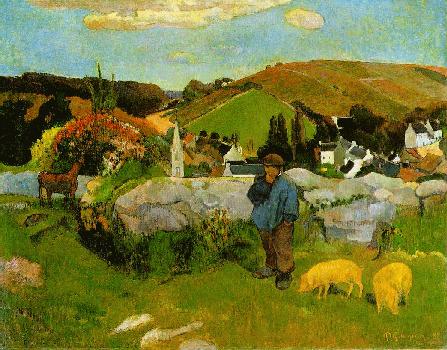

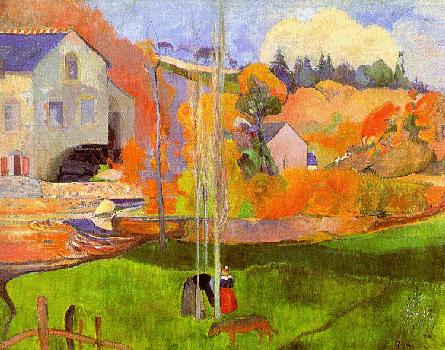

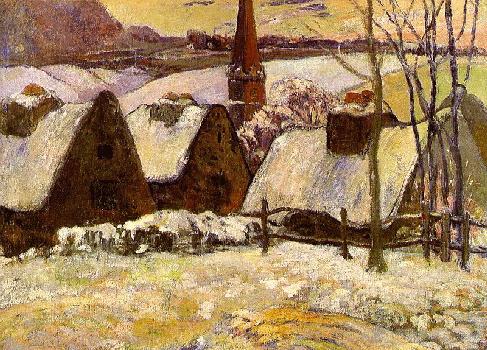

While Viaud presents Brittany, like the North Atlantic, as a place of almost constant mist and fog, not all artists saw it like this.

It is interesting to note, for example, that Gauguin, who made his famous trip to Tahiti in part because he was inspired by Loti's earlier novel, The Marriage of Loti, presented Brittany in his art in a very brightly lit, clearly focused fashion, as these paintings illustrate.

Not all of Iceland Fisherman is set in the North Atlantic and Brittany, however. When Sylvestre Moan, one of the members of the Marie's crew, arrives in Viet-nam as part of his military service at the beginning of Part III, his world changes entirely. So, appropriately, does the style of the novel. Gone is the soft impressionism used to describe Brittany and the North Atlantic. Viaud replaces it with a world of primary colors, bright light, and violence. (See, in particular, Part III, Chapters 1 and 3.)

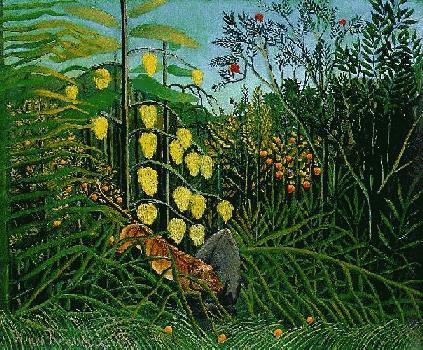

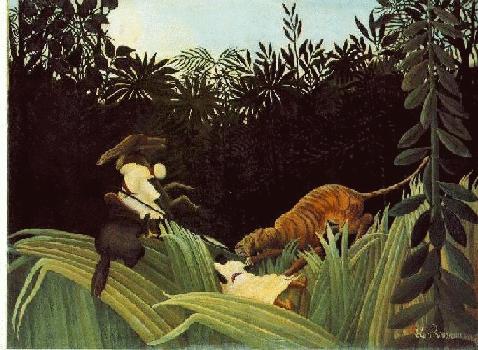

Again, there was a contemporary equivalent of this in the visual arts, in the works of French painter Henri Rousseau (1844-1910).

Rousseau's paintings, with their sharply defined forms, violent primary colors--and violence itself--and depiction of a jungle setting, are a perfect visual equivalent for the scene in Part Three, Chapter 1, where Sylvestre is shot during a military skirmish with "natives," and show how clearly Viaud managed a visual contrast to highlight the change in Sylvestre's world.