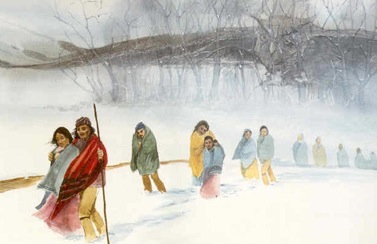

In 1835 Treaty of New Echota gave President Jackson the legal document he needed to remove the Cherokee. The treaty, illegally signed by a small minority of Cherokees known as the Treaty Party, relinquished all lands east of the Mississippi River in exchange for land in Indian Territory and the promise of money, livestock, various provisions and tools, and other benefits. Though few Senators vocally opposed the law, it passed by a single vote and the ratification sealed the Cherokee’s fate. The extradition was initially delayed by General Wool’s resignation, but General Winfield Scott arrived at New Echota on May 17, 1838 with 7000 men and early that summer began the invasion of the Cherokee Nation. Entire families were taken from their land, herded into makeshift forts with minimal facilities and food, then forced to march a thousand miles under cruel conditions. These long, cold marches, difficult at best, were made worse by shortages of wagons, horses, blankets and food. Woefully inadequate funds were quickly exhausted, and it resulted in a high number of Cherokee deaths. Cherokee Chief John Ross made an urgent request to General Scott to let his people lead the tribe west. Ross organized the Cherokee into smaller groups and let them move separately throughout the wilderness so they could search for food. Although the parties under Ross departed in early fall and arrived in Oklahoma during the brutal winter of 1838-39, he significantly reduced the loss of life among his people. About 4000 Cherokee died as a result of the removal. The route they traversed and the journey itself became known as "The Trail of Tears" or, as a direct translation from Cherokee, "The Trail Where They Cried" ("Nunna daul Tsuny").

Chief John Ross, who valiantly resisted the forced removal of the Cherokee, lost his wife Quatie in the march. When the pro-removal Cherokee leaders signed the Treaty of New Echota, they also signed their own death warrants. The Cherokee Naiton Council earlier had passed a law that called for the death penalty for anyone who agreed to give up tribal land. The signing and the removal led to bitter factionalism and the deaths of most of the Treaty Party leaders once in Indian Territory. And so a country formed fifty years earlier on the premise "...that all men are created equal, and that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, among these the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.." brutally closed the curtain on a culture that had done no wrong. Although the tribes in their new Oklahoma territories never recovered the vitality of the old days, they did reassert their former way of life, albeit in somewhat diminished form. They established farms, built schools and churches, revived their political institutions, and the Cherokees resumed publication of their newspaper.

To return to the home page, click here.

To read poetry written about “The Trail of Tears” click here.