Marine Fisheries Food Webs

Food Webs

All our ideas of life in the sea are rapidly changing. The plants and animals described on this page are mostly large. Yet, the marine food web is dominated by astronomical numbers of micro, nano, and pico plankton described in the chapter on the Microbial Food Webs. We know little about these organisms. They are too small to be easily seen and studied. They cannot be cultured. They tend to all look alike.

We can separate marine microbes using DNA analysis, and the analysis is leading to remarkable discoveries. Life in the sea is much more diverse than we expected. For example, we now know, since the 1970s that all life is separated into three domains. All three are very common in the ocean. Click on any of the three domains and explore the microscopic world.

Since the discovery of the astronomical number of microbes in the ocean, we now recognize two important, overlapping food webs in the ocean.

- The microbial food web discussed in that chapter. This web dominates the carbon, nitrogen, and other nutrient cycles of the earth system.

- The marine fisheries food web discussed here.

The two webs are coupled in many ways that are not yet understood. Microbes cycle nutrients, they produce other nutrients such as vitamins needed by primary producers discussed here, and they infect, sicken, and kill many organisms in the marine fisheries food web. We are not the only large animals that get viral and bacterial diseases.

Phytoplankton: Primary Producers of the Marine Fisheries Web

The sunlit upper layers of the ocean, called the euphotic zone, are home to vast numbers of single-cell marine primary producers called phytoplankton. They include diatoms, coccolithophores, cyanobacteria especially synechococcus and prochlorococcus, and dinoflagellates. Of these major classes of organisms, all but the cyanobacteria are eukaryotes, organisms with cells with a nucleus. Microscopic, eukaryota phytoplankton were formerly lumped together under the term protists, but this is a catch-all term.

Recent studies of protist DNA and ultrastructure has shown that the protists are far more diverse than had been previously expected; they probably should be classified in several kingdom-level taxa. We retain the word "protist" as a convenient term to mean "eukaryote that isn't a plant, animal, or fungus.

From Eukaryota: Systematics.

The term algae is another catch-all term for primary producers with chlorophyll that formerly included many unrelated organisms, excluding land plants.

Phytoplankton are primary producers because they use solar energy to convert CO2 and nutrients into carbohydrates and other molecules used by life. Together, they account for about 95% of the primary productivity in the ocean and about half of all primary productivity on earth.

Phytoplankton are most common in cooler, mid-latitude zones with sufficient nutrients, especially nitrogen. Thus they are common in the north Atlantic and Pacific, and along coasts. They are much less common in the central regions of the ocean and in the southern hemisphere. For more information, see the chapter on phytoplankton distribution.

The major primary producers include:

- Diatoms. They dominate the temperate and polar oceans. Typical size is about 30 micrometers. They contribute about 60 per cent of the primary productivity in the oceans.

- Coccolithophores. They dominate in regions of moderate turbulence and nutrients such as mid-latitudes in late spring in subpolar regions and in equatorial regions. Typical size is 5-10 micrometers in diameter. They are one of the world’s major primary producers, contributing about 15 per cent of the average oceanic phytoplankton biomass to the oceans (Berger, 1976).

- Cyanobacteria. Typical size is about 1 micrometer in diameter. The most common are prochlorococcus and synechoccis.

- Dinoflagellates.They tend to dominate in regions of low turbulence and nutrients, such as oceanic areas in late summer. Sizes range from 30 micrometers for some marine species up to 2,000 micrometers (2 mm) for Noctiluca.

Example: Diatoms are single-celled organisms with a nucleus (unicellular, eukaryotic organisms) capable of converting sunlight into carbohydrates. The diatoms are located near the bottom of the Tree of Life. They belong to the Stramenopiles which are included in the chromalveolates supergroup of the eukaryotes. The relationships among the phytoplankton and organisms near the base of the tree of life is not yet well understood (see the Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships) and the primary interrelationships are just now becoming clear. There are perhaps 200,000 different species of diatoms ranging is size from micrometers to millimeters. Some are no more closely related than fish and mammals (Armbrust 2009). They account for 20% of the photosynthesis on earth.

The skeleton of a diatom, or frustule, is made of very pure silica coated with a layer of carbon-based material. This skeleton is divided into two parts, one of which (the epitheca) overlaps the other (the hypotheca) like the lid of a box or petri dish. Observe the diatom frustule below, in which the two halves have been pushed slightly askew.

From University of California, Berkeley, Museum of Paleontology, phylogeny wing's page on Diatoms.

Zooplankton

The phytoplankton are eaten by the smallest floating animals, the zooplankton. They range in size from single-celled organisms to larger multi-celled organisms. Small zooplankton are eaten by larger zooplankton. Zooplankton include

- Single-celled animals such as ciliates or amoeboids that never grow large.

- Copepods.

- Shrimp.

- Larval forms of barnacles, molluscs, fishes, and jellyfish, all of which grow to be much larger animals.

Example: Copepods

The copepods are a class of crustaceans with over 7,500 species, most of which are marine. Copepods are small (only a few species over 1 mm) and extremely abundant, often dominating the plankton community. They form a link in the food web between the primary-producing phytoplankton and the plankton-feeding fish like Atlantic herring. Almost all fish found in temperate and polar waters rely at some point in their life cycle on copepods and other shrimp-like zooplankton (krill) as a food source.

From Atlantic herring.

Paraeuchaeta norvegica, a carnivorous copepod commonly found in fjords and North Atlantic waters. Click on image for a zoom. This beautiful photo was taken by Hege Vestheim of the University of Oslo.

From University of Oslo, Department of Biology, Images.

Small Predators

Zooplankton are eaten by small predators:

- Shrimp and krill.

- Immature stages of larger animals such as jellyfish and fish.

- Small fish such as sardines, menhaden, and herring.

Example: Clupeus harengus (Atlantic herring) is a small bait fish. It schools in coastal waters. It feeds on small planktonic copepods in the first year, thereafter mainly on copepods. Adults are about 30-35 cm in length, and they live about 20 years. They are eaten by many species of birds, fish, and marine mammals.

From Food and Agriculture Organization via Fishbase.

Top Predators

At the top of the marine food web are the large predators:

- Jellyfish and cephalopods (squid and octopus).

- Large fish such as sharks, tuna, and mackerel.

- Marine mammals including seals, walruses, dolphins, and some species of whales (some eat fish, others eat zooplankton directly).

- Birds such as pelikans, albatross, penguins, and skua.

- People, the dominant top predator.

Example: Thunnus alalunga (Albacore) is large, fast-swimming fish. Their average weight is about 9-20 kg. They are thought to become sexually mature when they are 5-6 years old and about a meter long. They have a maximum lifespan of 8 years. They are well adapted to swim fast, and they prey on many species of fish.

From Food and Agriculture Organization via Fishbase.

Food Chains and Food Webs

Phytoplankton, small zooplankton, larger zooplankton such as jellyfish, larger animals including bait fish and squid, (see also here), and top predators such as tuna, all interact in a marine food web. Each species eats and is eaten by several other species at different trophic levels.

Big fish eat little fish; that’s how the food cycle works. Of course, there’s more to it than that. A whirlwind spiral up the marine food chain goes like this: Phytoplankton—microscopic plants drifting in the water—feed the copepods and other grazers that feed the small menhaden and crustaceans that feed the stripers and bluefish that feed the tunas and swordfish that feed us.

From The Marine Food Web by Tony Corey and David Beutel

The interactions in a food web are far more complex than the interactions in a food chain. Furthermore, the branching structure of food webs leads to fewer top predators compared with the numbers of top predators in a food chain.

An example of a simplified food web, which defines the various elements of such webs (‘functional groups’), the flow between them, and so-called ‘trophic levels’, which indicate the position of each functional group within the web.

From "Fishing down marine food webs' as an integrative concept" by Daniel Pauly (University of British Columbia, Canada), Proceedings of the EXPO'98 Conference on Ocean Food Webs and Economic Productivity, online at the Community Research and Development Information Page.

Using the illustration above, a food chain would go from phytoplankton to large zooplankton such as krill to marine mammals such as baleen whales with no branches. Food chains are much rarer than food webs in marine ecosystems, although the example I just gave which leads to baleen whales is a common food chain in the Antarctic Circumpolar Current.

Over Fishing Changes Food Webs

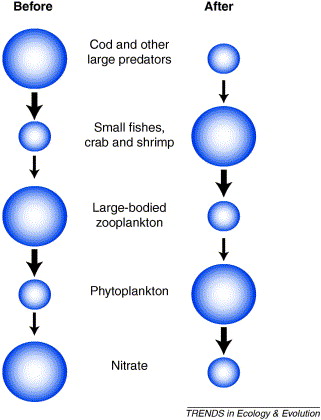

We saw earlier that Cod stocks on Canada's East Coast have failed to rebound more than a decade after the fishery was closed. Now, Kenneth Frank and colleagues have reported the results of their study of changes in the food web in the large eastern Scotian Shelf offshore of Nova Scotia, Canada. They found that the removal of cod and other large fish changed the entire structure of the food web from top to bottom:

- The population of small fishes and large invertebrates, including northern snow crab and northern shrimp increased markedly.

- The population of large plant-eating zooplankton (> 2 mm) decreased markedly.

- Phytoplankton increased markedly.

- Seal populations are increasing exponentially.

- The economic value of the crab and shrimp fisheries now exceeds the earlier value of the cod fishery.

- Actions to restore the cod fishery have failed despite a nearly complete shutdown of cod fishing.

- Cod stocks in other areas north of 44 degrees North have also failed to recover, while cod stocks in areas south of 44 degrees North have started to recover.

The cascading effect of the collapse of cod and other large predatory fishes on the Scotian Shelf ecosystem during the late 1980s and early 1990s. The size of the spheres represents the relative abundance of the corresponding trophic level. The arrows depict the inferred top-down effects.

From Scheffer (2005).

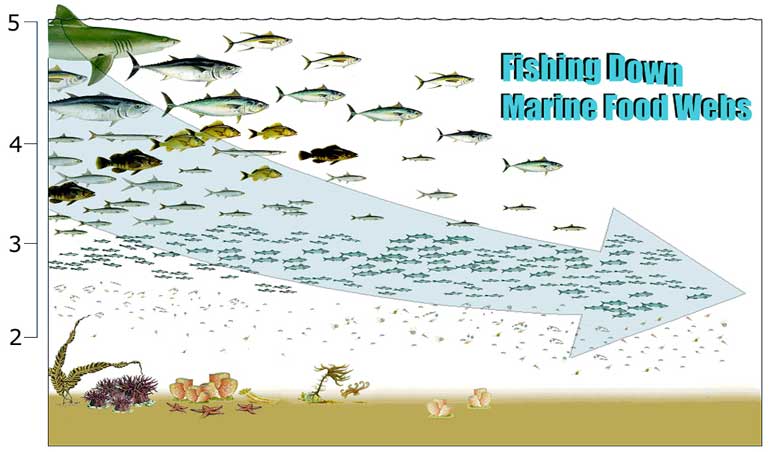

The changes in marine ecosystems due to over fishing is often called fishing down the marine food web. As top predators are removed by fishing, fishers target smaller fish lower in the food web, reducing their numbers. This reduces the average trophic level of the food web. Trophic levels are based on the food eaten at that level. Level 1 includes phytoplankton, level 2 includes zooplankton, level 3 includes bait fish, etc.

Fishing down the marine food web. After the

large fish at the top of the food web are fished out, fisheries go after

smaller fish and invertebrates at lower levels in the food web while

their trawling destroys animals and plants on the sea floor. Time

increases toward the right along the blue arrow. Scale on the right gives

the trophic level in the food web.

From Pauly (2003).

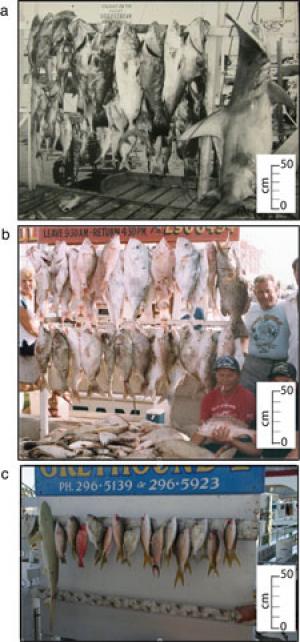

Scripps Institution of Oceanography graduate student Loren McClenachan studied historical photographs spanning more than five decades that she collected from Florida. The study showed a drastic decline of so-called "trophy fish" from Key West.

Photographs showing trophy fish caught on Key West charter boats a) 1957, b) early 1980s, and c) 2007.

From Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Historical Photographs Expose Decline in Florida's Reef Fish, New Scripps Study Finds.

References

Armbrust, E. V. (2009). The life of diatoms in the world's oceans. Nature 459 (7244): 185–192.

Berger, W. (1976). Biogenous deep-sea sediments: production, preservation and interpretation. In J.P. Riley, R. Chester (eds.), Treatise on Chemical Oceanography. Academic Press, London, pp. 265-388.

Pauly, Daniel (2003). Ecosystem impacts of the world's marine fisheries. Global Change Newsletter, 55, page 21.

Scheffer, M., S. Carpenter, et al. (2005). Cascading effects of

overfishing marine systems. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 20(11):

579-581.

Profound indirect ecosystem effects of overfishing have been shown for coastal

systems such as coral reefs and kelp forests. A new study from the ecosystem

off the Canadian east coast now reveals that the elimination of large predatory

fish can also cause marked cascading effects on the pelagic food web. Overall,

the view emerges that, in a range of marine ecosystems, the effects of fisheries

extend well beyond the collapse of fish exploited stocks.

Revised on: 27 May, 2017