Oil Spills

Overview

The Ocean Studies Board and Marine Board of the National Academy of Sciences has published Oil in the Sea (2003) which summarizes sources of oil pollution:

Nearly 85 percent of the 29 million gallons of petroleum that enter North American ocean waters each year as a result of human activities comes from land-based runoff, polluted rivers, airplanes, and small boats and jet skis, while less than 8 percent comes from tanker or pipeline spills.

Average annual contribution to oil in the ocean (1990-1999) from major sources of petroleum in kilotonnes.

From Oil In The Sea, Ocean Studies Board and Marine Board of the National Academy of Sciences (2003).

The major sources of petroleum in the sea, in order of importance, include:

- Natural seeps from rocks below the sea floor. Oil seeps are common

in many areas, including the Gulf of Mexico and offshore of Southern

California, and in other areas where oil is found beneath the continental

shelf.

Radarsat image of oil seeps near Green canyon in the Gulf of Mexico. The oil reaching the sea surface produces a slick that reflects little radio energy, seen as black lines in this image. Radarsat is a Canadian satellite that uses a synthetic-aperture radar to map radio waves reflected from the sea surface.

From MDA's Geospatial Services.

- Consumption, which includes runoff from land and oil from marine

boating and jet skis in coastal waters. Most cars drip oil on streets

and highways which is washed off by rains. The millions of cars in

large coastal cities are important sources.

The dark band in the center of the lanes on this highway are caused by oil dripping from countless cars that travelled along the U.S. 49 northbound in the vicinity of Florence, Mississippi.

From Southeast Roads.

- Transportation, which includes spills from tankers and pipelines as well as intentional discharge from ships at sea.

- Extraction, which includes spills from offshore platforms and blowouts

during efforts to explore for and produce oil and gas. An example

is the IXTOC

I oil well blowout in the Bay of Campeche, Mexico, June 1979 to

March 1980, which released 476,000 tonnes of crude oil into the Gulf

of Mexico.

The Itox 1 exploratory well in the Bay of Camphece blew out on 3 June 1979 causing a major oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. By the time the well was brought under control in 1980, an estimated 140 million gallons of oil had spilled into the bay. The IXTOC I is currently number 2 on the list of largest oil spills of all-time.

From Incident News.

Oil Spills

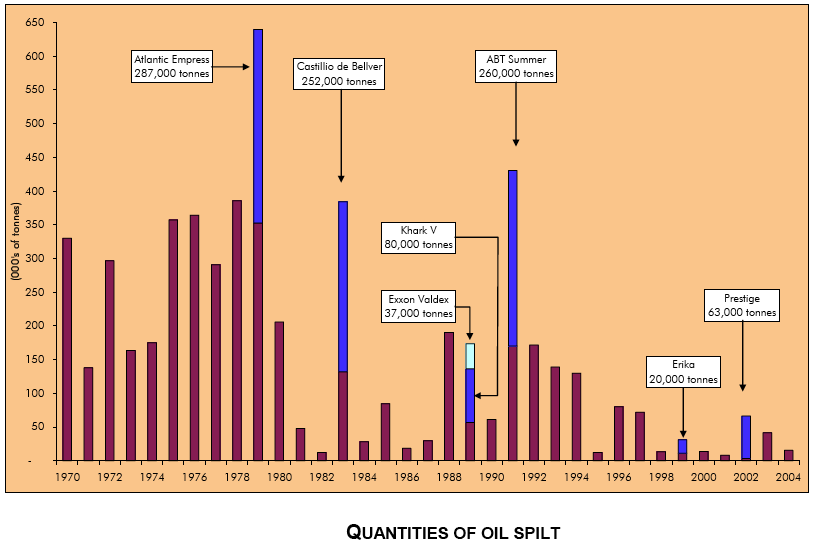

Oil spills from oil tankers operating at sea world-wide account for only 7.7% of oil in the ocean, yet large spills attract far more attention than other much larger sources of oil pollution. The International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation Historical Data has information on all spills, large and small. They note that "The average number of large spills per year during the 1990s was about a third of that witnessed during the 1970s."

|

Position |

Ship name | Year | Location |

Spill

Size (tonnes) |

|

1 |

Atlantic Empress | 1979 | Off Tobago, West Indies |

287,000 |

|

2 |

ABT Summer | 1991 | 700 nautical miles off Angola |

260,000 |

|

3 |

Castillo de Bellver | 1983 | Off Saldanha Bay, South Africa |

252,000 |

|

4 |

Amoco Cadiz | 1978 | Off Brittany, France |

223,000 |

|

5 |

Haven | 1991 | Genoa, Italy |

144,000 |

|

6 |

Odyssey | 1988 | 700 nautical miles off Nova Scotia, Canada |

132,000 |

|

7 |

Torrey Canyon | 1967 | Scilly Isles, UK |

119,000 |

|

8 |

Sea Star | 1972 | Gulf of Oman |

115,000 |

|

9 |

Irenes Serenade | 1980 | Navarino Bay, Greece |

100,000 |

|

10 |

Urquiola | 1976 | La Coruna, Spain |

100,000 |

|

11 |

Hawaiian Patriot | 1977 | 300 nautical miles off Honolulu |

95,000 |

|

12 |

Independenta | 1979 | Bosphorus, Turkey |

95,000 |

|

13 |

Jakob Maersk | 1975 | Oporto, Portugal |

88,000 |

|

14 |

Braer | 1993 | Shetland Islands, UK |

85,000 |

|

15 |

Khark 5 | 1989 | 120 nautical miles off Atlantic coast of Morocco |

80,000 |

|

16 |

Aegean Sea | 1992 | La Coruna, Spain |

74,000 |

|

17 |

Sea Empress | 1996 | Milford Haven, UK |

72,000 |

|

18 |

Katina P | 1992 | Off Maputo, Mozambique |

72,000 |

|

19 |

Nova |

1985 | Off Kharg Island, Gulf of Iran |

70,000 |

|

20 |

Prestige* | 2002 | Off the Spanish coast |

63,000* |

|

35 |

Exxon Valdez | 1989 | Prince William Sound, Alaska, USA |

37,000 |

Figure and table are from International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation compilation of historical data.

Cleaning Up After Oil Spills

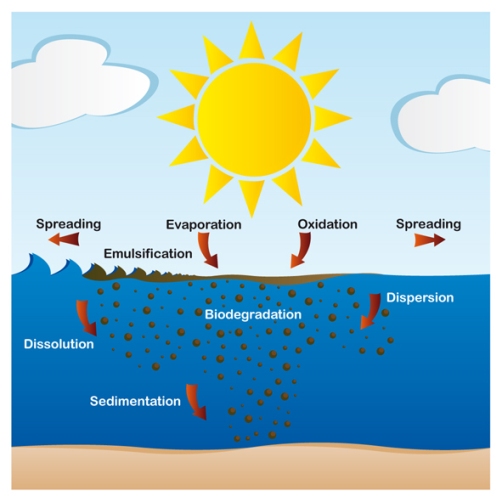

No two oil spills are the same because of the variation in oil types, locations and weather conditions involved. However, broadly speaking, there are four main methods of response.

1. Leave the oil alone so that it breaks down by natural means.

2. Contain the spill with booms and collect it from the water surface using skimmer equipment.

3. Use dispersants to break up the oil and speed its natural biodegradation.

4. Introduce biological agents to the spill to hasten biodegradation.From Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association.

Oil spill have an immediate effect on marine life, and a longer term effect. The International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation lists Effects of Oil Spills. They include:

- Biological, including physical effects such as smothering and the

influence of toxic chemicals.

Simply, the effects of oil on marine life, are caused by either the physical nature of the oil (physical contamination and smothering) or by its chemical components (toxic effects and accumulation leading to tainting). Marine life may also be affected by clean-up operations or indirectly through physical damage to the habitats in which plants and animals live.The main threat posed to living resources by the persistent residues of spilled oils and water-in-oil emulsions ("mousse") is one of physical smothering. The animals and plants most at risk are those that could come into contact with a contaminated sea surface. Marine mammals and reptiles; birds that feed by diving or form flocks on the sea; marine life on shorelines; and animals and plants in mariculture facilities.

The most toxic components in oil tend to be those lost rapidly through evaporation when oil is spilt. Because of this, lethal concentrations of toxic components leading to large scale mortalities of marine life are relatively rare, localized and short-lived. Sub-lethal effects that impair the ability of individual marine organisms to reproduce, grow, feed or perform other functions can be caused by prolonged exposure to a concentration of oil or oil components far lower than will cause death. Sedentary animals in shallow waters such as oysters, mussels and clams that routinely filter large volumes of seawater to extract food are especially likely to accumulate oil components. Whilst these components may not cause any immediate harm, their presence may render such animals unpalatable if they are consumed by man, due to the presence of an oily taste or smell. This is a temporary problem since the components causing the taint are lost (depurated) when normal conditions are restored.

From Effects of Marine Oil Spills

Processes influencing weathering of oil in the sea.

From Behavior of Oil at Sea.

- Destruction of coastal habitats.

- Damage to boats and gear used for fishing, and loss of market for fish if buyers suspect the fish may be contaminated by the oil spill.

The long-term damages are more benign.

- Smaller, more volatile molecules in oil quickly evaporate or oxidize. These molecules are the most toxic to life.

- Larger, less volatile molecules are not toxic. We put asphalt, which is mostly the larger oil molecules, on roads and driveways and grass grows through the cracks in the asphalt. And, the asphalt quickly oxidizes. Few roads are useful after a decade because the asphalt oxidizes, hardens, and breaks up. The asphalt must be replaced.

- Tar has been used for many purposes for centuries with little ill effect.

Lessons Learned

We have learned much from previous oils spills. What can we do to minimize environmental damage? Sometimes the clean up is worse than the spill. The NOAA has been monitoring Prince William Sound, the location of the spill, and they have amassed information on Results, Lessons Learned.

- Set aside areas that have not been cleaned to compare with cleaned areas to assess usefulness of cleaning.

- High-pressure, hot-water cleaning causes short-term and long-term damage.

- Stating that cleanup does "more harm than good" while to some

extent true, is a bit of an oversimplification. Still, we have learned

that:

- The use of detergents, which are toxic to marine life, to disperse the oil.

- The use of steam and hot water to clean rocks, which kills

all organisms on the rocks.

Current evidence implies that oiled and hot-water washed sites initially suffered more severe declines in population abundance than oiled and not-washed sites.

From NOAA.

- Any cleanup that changes the physical makeup of the area delays recovery. In particular, Large scale excavation of gravel beaches, which delays recovery for many years.

- Oil that penetrates deeply into sand or sediments can stay fresh for years and be released slowly back into the water. Cleanup is difficult because it disrupts the physical state of the area. Recovery is delayed many years.

- Using water to flush away oil may remove fine sediment needed by organisms.

Results of studies of major British oil spills at sea by the British Marine Life Study Society. By 2001 a survey by Auke Bay Laboratory found only 20 acres of beach contained oil residues, all buried below the surface of the beach (Alaska Fisheries Science Center: The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill: How Much Oil Remains?).

See the yearly photographs of Means Rock to understand the difficulty of determining if an area has returned to normal.

Other Information

NOAA has a useful site for students and teachers with much useful information.

Amaco Cadiz, the world's fourth largest largest oil spill, after 20 years. Very few problems: However, this oil slick has become an old memory for the fishing and tourism industries and for the other economical activities...The shipwreck has become a new “home” for fishes and crustaceans and a place to explore for experienced divers.

References

Ocean Studies Board and Marine Board (2003). Oil

in The Sea III: Inputs, Fates, and Effects. Washington DC:

The National Academies Press.

Revised on: 29 May, 2017