Caligu-Li, Caligu-La

In 1979, Avon — the cosmetics company responsible for trinketized perfumes, shampoos, bath oils, soaps, and more sold door to door — offered as one of their uber-collectible items a small series of blue Greco-Roman vases, adorned with cutesy portraits of women in togas. One of them, now culturally reduced to a flea market delight, sits atop my bookshelf, with the original packaging on my bedside table; apparently, it once housed ‘Somewhere Cologne’. Now, it just sits there, some old sewing patterns leaning against it, cherub-like children playing under a tree across its rounded surface.

Whether the wholesome folks at Avon had Caligula in mind when they designed the pieces is unclear, though the film had been building hoopla over the course of almost four years upon its initial release in that very year. They were probably just adding a new flavor of nostalgia to their lineup of glamorous bottles, Aladdin’s lamps, old-timey cars, and owls. The American broadcast of the wildly successful television series of Robert Graves’ I, Claudius was not too distant in cultural memory, so perchance that work’s ode to the political scheme and colorful characters of ancient Rome was a subconscious influence. Maybe they were really excited for Xanadu.

Unlike Xanadu, Caligula does not have an extremely catchy theme song sung by Olivia Newton-John[1]; it does, however, have Malcolm McDowell doing a strangely serious victory-dance numerous times, as well as, in its newest iteration, a droning and ominous synthesized hum that soundtracks its uncanny images of lonely grandeur. Rome, to Gore Vidal — er, Tinto Brass — er, Bob Guccione, is a soundstage, an alien planet.

This atmosphere is multi-dimensional. The film itself holds an uncanny spot in cultural history, is perceived by those who recall it as having been made by minds on some higher level, the last surviving participants in some lost civilization. It boasts one of the most infamous behind-the-scenes stories of any film out there; it’s the sort of film whose scriptwriter — Vidal — and director — Brass — did not want their names attached to whatsoever. Completely unrelated pornographic scenes were inserted throughout by Guccione, the film’s producer and founder of Penthouse Magazine. And so on.

Those scenes are not present in this new version of Caligula. Helmed by art historian Thomas Negovan, it is dubbed the Ultimate Cut, which is a name I find totally corny and useless, though it is inherently noble in its attempt at restoring Vidal’s original script as closely as possible. This, of course, is impossible, since that script focused heavily on homosexual scenes that were written out by the time filming began; however, that is not to say that one can’t try.

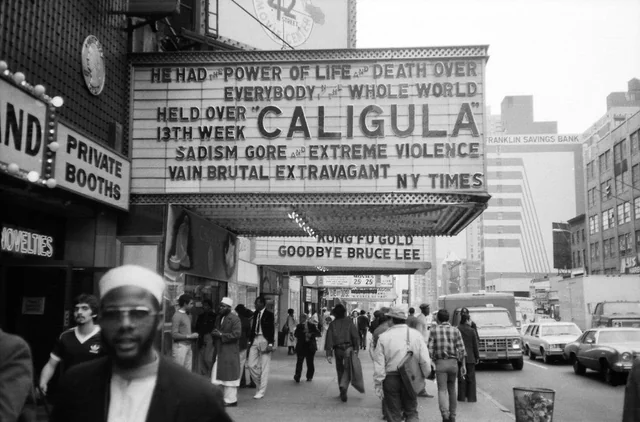

I knew of Caligula’s history roughly, or more so its reputation as lurid and, in many assessments, poorly. But the historical significance of its existence is quite different than some comparable works owing to its medium. Films are costly to make, and Guccione genuinely sought to pioneer both the presence and normalization of hardcore materials in mainstream film. And while you can still easily find a copy of Blind Faith at your local record store, or Fanny Hill at Salvation Army, film distribution is much trickier and many true classics can only be viewed nowadays by purchasing a copy that has been out of print for decades, or happening upon a screening in a town cultured enough to have a hip theatre with an ongoing hip classic-film series.

Despite its rich cultural history, Kent, Ohio is normally not one of those towns, unless it’s the monthly Rocky Horror screening at the Kent Stage (the line goes down the entire Main Street block on Halloween). And while the Nightlight and the Highland Square Theatre in Akron both play a plethora of films, popular and obscure, old and new, not all college kids have the car needed to get there. You have to suffice for the MovieScoop a quick Downtowner bus ride south of town, where I recently saw Frankenstein, which was just slightly offensive to me as someone who had actually read the book. So when I learned that this new cut of Caligula was being screened at the Stage, a ten-minute Campus Loop sit away, I flipped. This was the utopia that Richard Myers of Akran and Deathstyles fame was building when he screened Fellini Satyricon for film classes attended by Mark Mothersbaugh, resurrected from long-buried rubble. (Of course, I was one of about a handful of people there, which is disappointing, though the male-half of the couple behind me did stop making comments to the lady-half after I shushed him.)

We open with a short animated dream-prologue, and then abruptly we are sucked into the wonderful world of Caligula; we learn very quickly that the woman cuddled up with the emperor is his sister, and it only gets more colorful from there. Quickly I settled into the reality this film constructs across its many luscious sets — every scene feels utterly self-contained, a moment in time captured in a jar, in a subconscious freeze-frame, yet each feels so alive. Some have complained about the film staying past its welcome — there were quite a few false-climaxes for me — but to me every second felt perfect and earned. I had to keep reminding myself as I watched that this was not a film crafted decades ago — no, this was reconstructed by hand in very recent years, reanimated with care and love. Watching this film for the first time with this presentation was a truly phantasmagoric experience, like stepping into an Orphean mirror world where everything moves simultaneously in slow motion and at exactly the right pace to digest it. Once I had adjusted to it, I felt fully immersed.

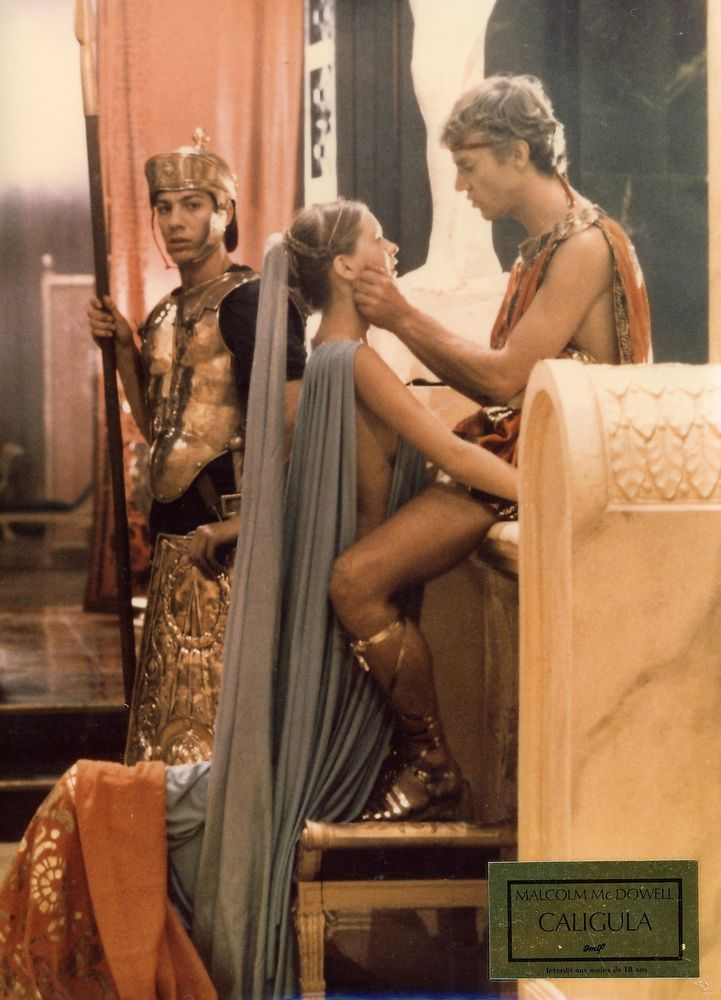

Perhaps no other film exhibits a greater appreciation for the human form. “This film’s costumes were obviously designed by a man,” I thought as I examined the ridiculous coils of silver wrapped seductively around the muscular arms of extras. Danilo Donati, the costumist who also outfitted numerous Fellini films including Satyricon and Casanova, Zeffirelli’s Romeo & Juliet, and Salò or the 120 Days of Sodom, deserves to be a household name nowadays, especially given the brief renaissance of the middle film’s style that spread across the internet the other year. The strokes of gauzey color, the flow of fabrics, glitter and sequins and peacock feathers — the colors, oh the colors. Robin’s egg blue is the most prominent and consistent one, but the whole rainbow, in bright pastels, is on display across over three-thousand-five-hundred costumes, of which only one survived. Blinding white sometimes whets the eyes, but there is always a painting box of finery on hand to defile it.

There is a comic-book like quality to Caligula, with its surreality and the strange perfection of every shot, yet there is a strange humanity underlying that unearthliness. It is an undercurrent that guides the film through its many vignettes, and McDowell’s performance in the title role, as intense and terrifying as it is self-possessed and alluring, is the harborer of this quality. His evolution from somewhat virtuous to monstrous is so subtle as to be barely present. The youthful vigor and striving spirit he exhibits in early scenes is perfectly foiled — and utterly quenched — by Peter O’Toole’s Tiberius; the aged emperor is clearly stoned and physically decrepit, visibly riddled with venereal disease yet still wrapping himself in gold-trim robes and surrounding himself with undressed women. There is much to be said about fate in this film, and if its portrayal of Tiberius says anything, it is that Caligula is doomed from the start. The not-so-prodigal grandson’s nightmares are much more than his own subconscious working against him; they are a reflection of his reality.

Any true innocence that Caligula harbors is very quickly plowed by blood-lust, yet he is still fully capable of entering boyish sprints in moments of inspiration, embarking on a game of Simon-says at a banquet, eliciting sheep noises from his Senate, or casually fondling the breast of whichever woman he is closest to. Helen Mirren’s Caesonia, who becomes his wife a ways into the film despite being ‘the most promiscuous woman in Rome’, is often the target of such cupping, not that she seems to care beyond poised amusement. And if any man of any stature or hubris found himself with the actress partially nude strode across his lap, it would be only natural for him to utter to himself, “I’m a god!” as McDowell does here. This Caesonia is utterly graceful in her sexy stoicity, in no way a true challenge to Caligula’s power but a strong and distinct character nonetheless, clearly intelligent and aware of the position she holds in society. Teresa Ann Savoy’s Drusilla also has a degree of awareness — “but we’re in Rome!” — but not nearly as much personality; this makes sense given Caligula’s perception of his sister as a vessel through which he can feel carnally proud of himself and his bloodline.

This sort of intensity of the film’s commentary — on social, political, and emotional systems — is offset by its embrace of the delirium of heightened people in heightened situations. I was delighted to see how many positive comparisons the film has gotten to those of Ken Russell, the master of balancing beauty with the grotesque. (Mirren actually appeared a few years earlier in his excellent biographical film Savage Messiah, playing a suffragette who gets super naked, which I realized as I wrote this is a great way to introduce Russell in general.) I’d argue this film owes as much to, say, Satyricon as it does to him, especially his then-recent take on the eighteenth-century, Lisztomania — which got a nice spread in Penthouse’s rival, Playboy — with its opulence and vibrancy that shimmers like a field of sequins with every scene-dressing candle-salad object. The man was also wildly funny, as are Caligula’s subtle and perfectly times doses of humor: the silly marching-around, the emperor’s ludicrously premature announcement of the birth of his son, et al.

Legend will tell you there is an actual crowning of a baby in this film, during the scene in which Julia Drusilla is born; three separate pregnant actresses is the common statistic. While I was taken aback by the presentation of this event, the event itself did not faze me; I remember thinking how impressive the special effects were — even the baby’s head looked absolutely real! That doesn’t mean I wasn’t shocked, however; this was just one of the scenes that proves that Caligula not only pushed boundaries then but remains potent in inspiring the wildest imaginations of an audience that persists to this day. It is engrossed in the inherently unwieldy journey of discovering what an audience can and cannot take. The gall of the wedding scene in particular — I suppose if you know, you know — left me stunned beyond real emotion, forcing me to look back on it through the inherent humor of something so universally vile followed by something equally so yet even more ridiculous.

Other scenes have people engaging in degenerate acts for the sake of it in the background or full-blown orgies, often daring one to smile and squirm at once. Yet scenes like the assassination of Tiberius are filmed in a skillful manner that avoids to maximum effect; what other film finds strange beauty in asphyxiation, acts out these terse political power dynamics with such grace? The entire film is choreographed like a twisted ballet; perfect blocking accentuates the fluid, lively motion of bodies and muscles and the weapons they wield.

You can make some lazy blah-blah-blah statement about how ‘relevant’ its themes are or some other blah-blah, or sex in today’s age and blah-blah, but doing so would take away from the timeless effectivity of this film. It is as much about politics as it is about power and its exotic, panther-like glamour, a glamour that pounces out from complete darkness like a vengeful god. It is a three-hour historical epic of Biblical proportions and Myra Breckenridge implications, to allude to Vidal in tribute to both his book of that title and its own controversial film, which the author despised. I, however, love that film, and I love it in a similar way as to why I love Caligula: both are utterly revolutionary. What Myra did to the raunchy sex comedy in its bombast, Caligula did to the pompous, gilded epic, elevating to the level of scripture the myths that the cultural osmosis of history often reinforces. Much of the infamous emperor’s true ‘insanity’ has been put into question by source analysis; much of the history of his life was written generations following his death by those who sought to discredit his rule, a fate faced by all of his rank. Caligula’s inaugurating his horse to the position of consul, for example, never happened, and the concept of doing so was either entirely invented by these detached opponents or nothing more than an extended in-joke targeting the Roman Senate.

Of course, Incitatus is given the good-boy treatment he rightfully deserves in this film. And incest is a central plot point, though those allegations were actually ledgered at his interactions with his (three separate) sisters and not only Drusilla, though she was often singled out as his favorite. And why wouldn’t these strange, baffling, lurid things occur in the operatic life of Caligula, this mononymous childhood nickname of a man? When the facts will all be conflated with exaggeration and the secondary players’ names will be lost to time, why wouldn’t you go all out? If culture has rendered those of your rank disposable by suicide or political assassination, why wouldn’t you treat those around you as such? Why wouldn’t you spend the average-four years you’d receive as ruler of the world’s most powerful empire living not just as an emperor, but as something above human? Despite the many men and women who put manpower into this film, Caligula still comes across as highly individualistic; it extolls the great-man theory of history as much as it burns it, makes awe-inspiring firecrackers from the burning embers. It presents a world in which anyone can truly do anything, and it just so happens that that entire ethos exists within one man. Every generation, of any time, deserves this sort of combination, where those in the highest positions of power meet the lowest positions one can place one’s self.

The film does slow down a bit near its end — the side effect of placing big scene after big scene after big scene, and every scene in Caligula is big and bright. I was ill-prepared; I somehow did not realize the film was going to be three hours long, leaving me yawning, fidgety, and craving the snack I had not bought at the concession stand, all against my will, for the last thirty minutes or so. But it was perhaps as a result of this fighting state that Caligula’s most shocking scene, to me at least, was its conclusion, where the emperor is assassinated. I felt that knee-jerk reaction that get when I feel tears coming; there was something so astonishingly stupefying at seeing the spear and the blood and the look on his face. The brief, barely noticeable glimpse of Julia Drusilla, who never lived to see past the age of one, getting her head slammed against the ground did not help, but neither did the concept of this immortal story ending, fading to black; I could not bear to think that this film was going to be over and felt almost renewed at that realization. I was shaking my head, I was truly awe-struck; I did not want to leave this strange new world where anything was possible. Even I could do anything I wanted in this world! This is what sensation feels like — not some lowbrow screed against an easy target but a true, actual feeling! And the credits rolled, as they must do, always, every time.

[1] If you would like more Electric Light Orchestra in your art-film-going, there is a cut of Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasuredome set to the Eldorado record. If you’re more into the eighties-eighties than the seventies-eighties, the folks behind the Ultimate Cut also made a kind of brill April Fool’s Day post promoting an updated version of the film featuring ditties such as “Relax” by Frankie Goes to Hollywood, direct to eight-track.

Stills sourced from around the 'net