The Glimmering Spoils of Censorship

Open images in new tab for full size

Lillian Roxon is undeniably one of the most fascinating figures in rock history. Her 1969 Rock Encyclopedia is one of the pioneering documents of rock music as a legitimate cultural form. Across three continents and a myriad of publications large and underground, she rallied for groups that are now cult classics in her articles. For every positive trend-forecast regarding Peter Gabriel’s “Willow Farm” getup, there was an insult lobbed at Linda Eastman after her leaving the New York journalist scene, through which the two had became great friends, for Beatlemarriage — which, if my husband belonged to the largest pop group on the planet and was amidst in a horrendous depression over said group’s horrendous disintegration, I’d go cold turkey on the press, too. Thus is the mercurial nature of Lillian Roxon, friend to both Helen Reddy and Germaine Greer.

Now, when I’m not trying to keep the conclusion to my book from becoming a mini-rant about portions of Greer’s The Female Eunuch — how the hell did that happen — I’m usually applying my research-mode wills to less heady matters. This was the case for me the other night when I decided I’d look up Roxon and click around a bit and see if I could find another great snippet from her that didn’t make it into Robert Milliken’s incredible biography of her life, which was my formal introduction to her role as the noted ‘mother of rock’.

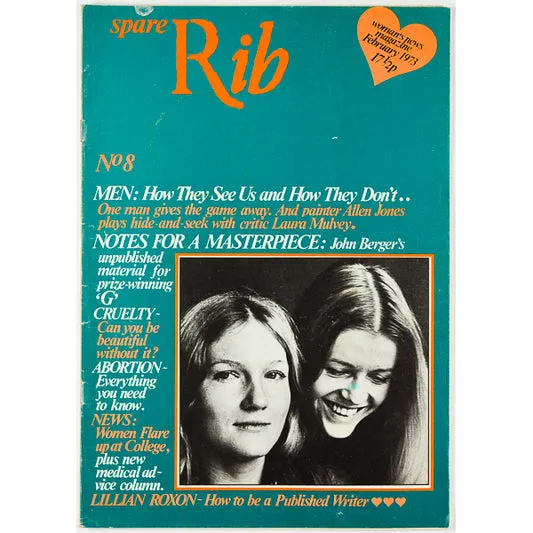

I did, in the form of this quip she made in Mademoiselle: “I’ve learned more about sex in a moment from reading the poems of Leonard Cohen and listening to his songs than I would ever have learned from Dr. Reuben or the Sensuous Man [sic].” But that’s besides the point, because along with this quote my DuckDuckGo search brought me the following innocuous scan of a magazine cover:

Spare Rib was quite the trailblazing ‘zine, representing the ideals of the then-burgeoning ‘women’s lib’ movement, of which Roxon was a part. And naturally I would like to read some career advice from one of the most fascinating female journalists in history. The British Library once had the magazine’s entire run digitized with free access for anyone, but they pulled it a couple years back owing to some Brexit related copyright complications, which I personally feel is a bit ridiculous given that Spare Rib was notable for adapting common women’s interest topics to reflect anti-capitalist, anti-consumerist ideologies that would most likely have aligned with the ideal of free or cheap dissemination of information to everyone, as well as the explicitly non-profit work of independent magazine archivists like Ryan Richardson. I use my own university’s library system frequently for research of all sorts, and was able to find a nice free archive of Oz on the University of Wollongong’s website, so I understand that for libraries it’s a bit different. Do I understand how the EU copyright exemption clause works specifically? Hell no. And since you can only get a free library Reader Pass in person across the pond, I guess they don’t want my twiddly American fingers on their sacred information anyway.

So I went to what it usually my first try when trying to scour down something with historical significance, which is the Internet Archive. A totally phenom website that should exist in perpetuity with its vast catalogue of scanned materials, archived films and radio shows, and ubiquitous Wayback Machine. Much of its uploaded materials don’t even require you to click the little free-checkout button; you can flip through zines of all political affiliations with nothing more than a few clicks — I should know, because I did a project for a class a few semesters back about the hardcore music of American white supremacist movements.

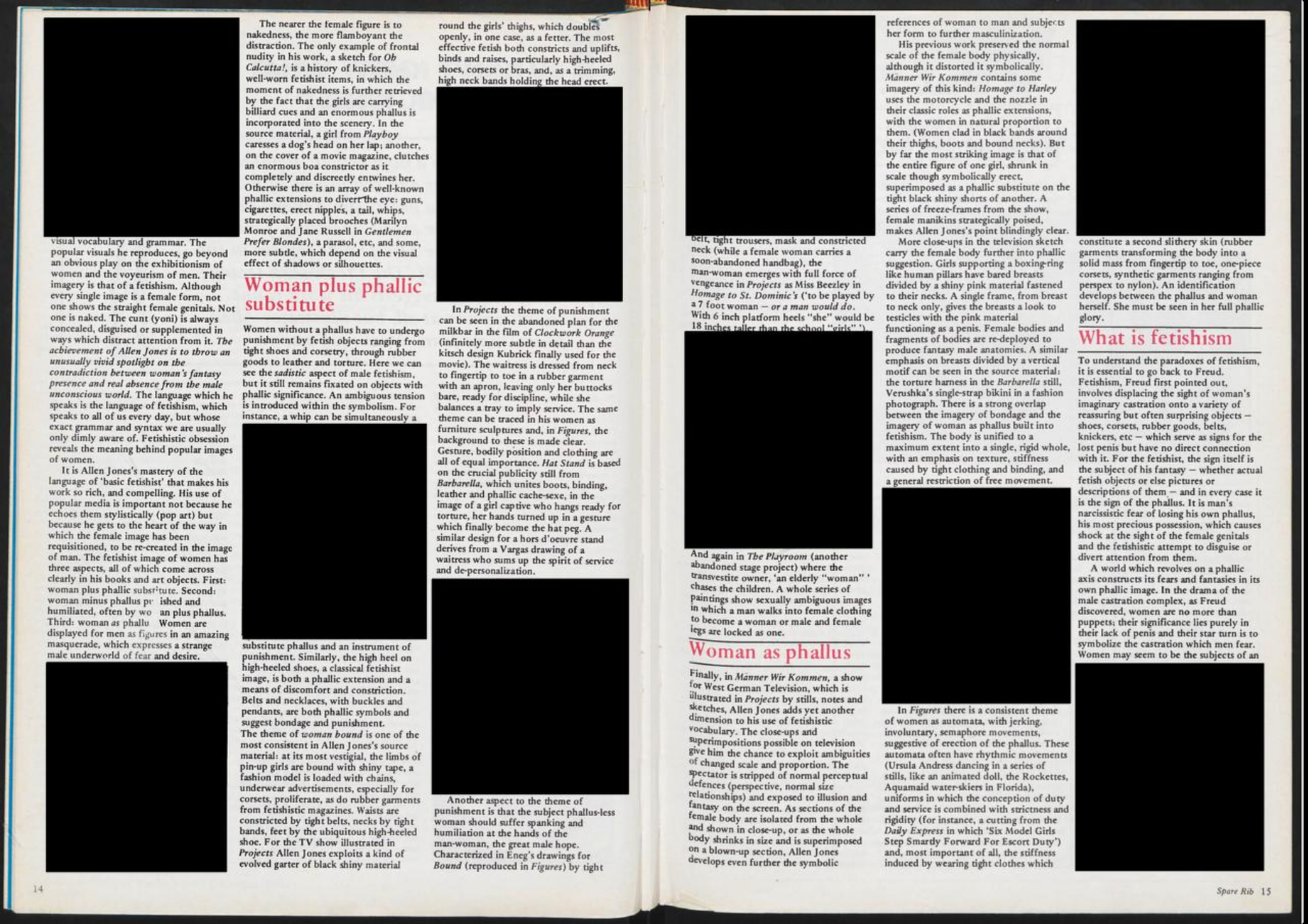

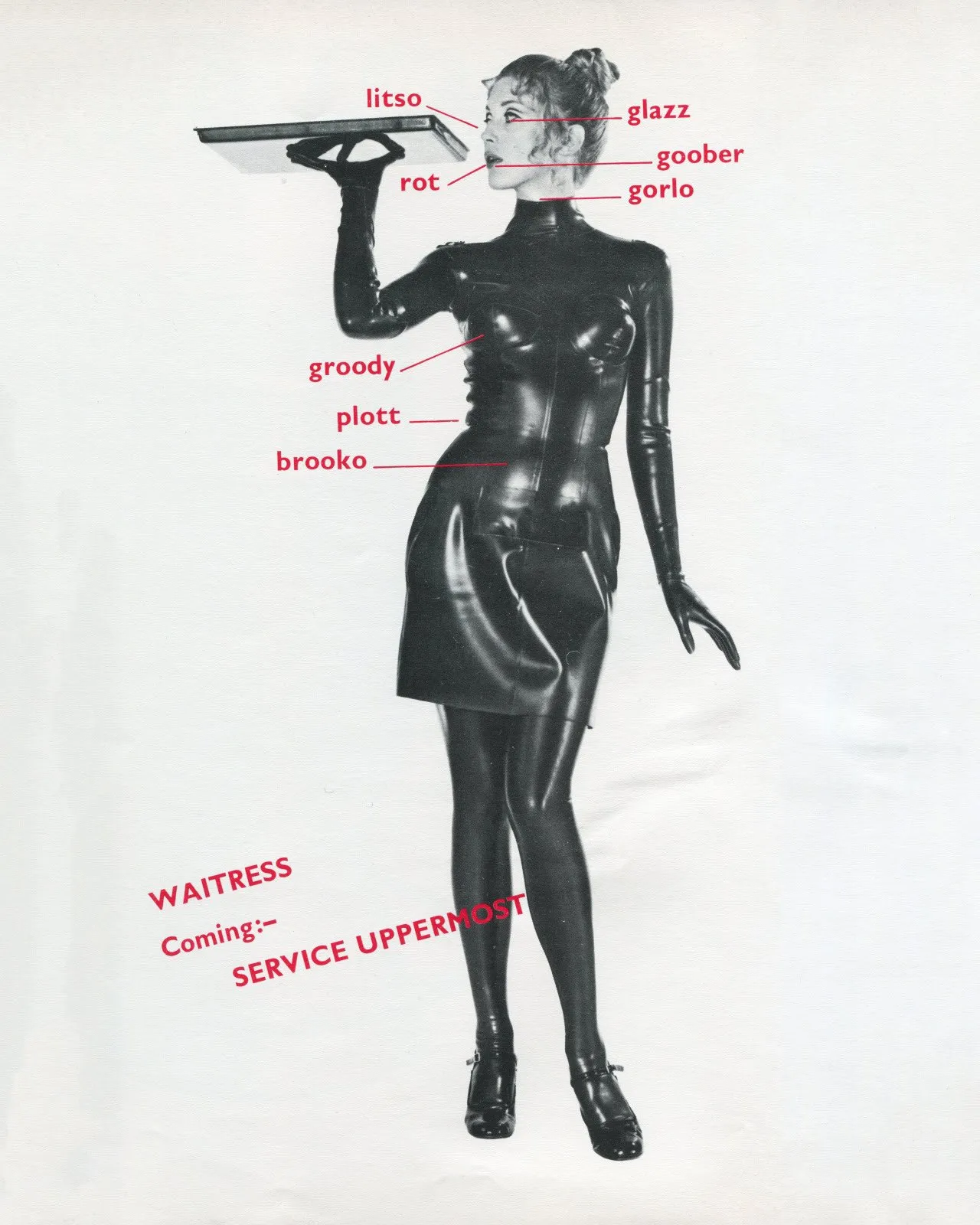

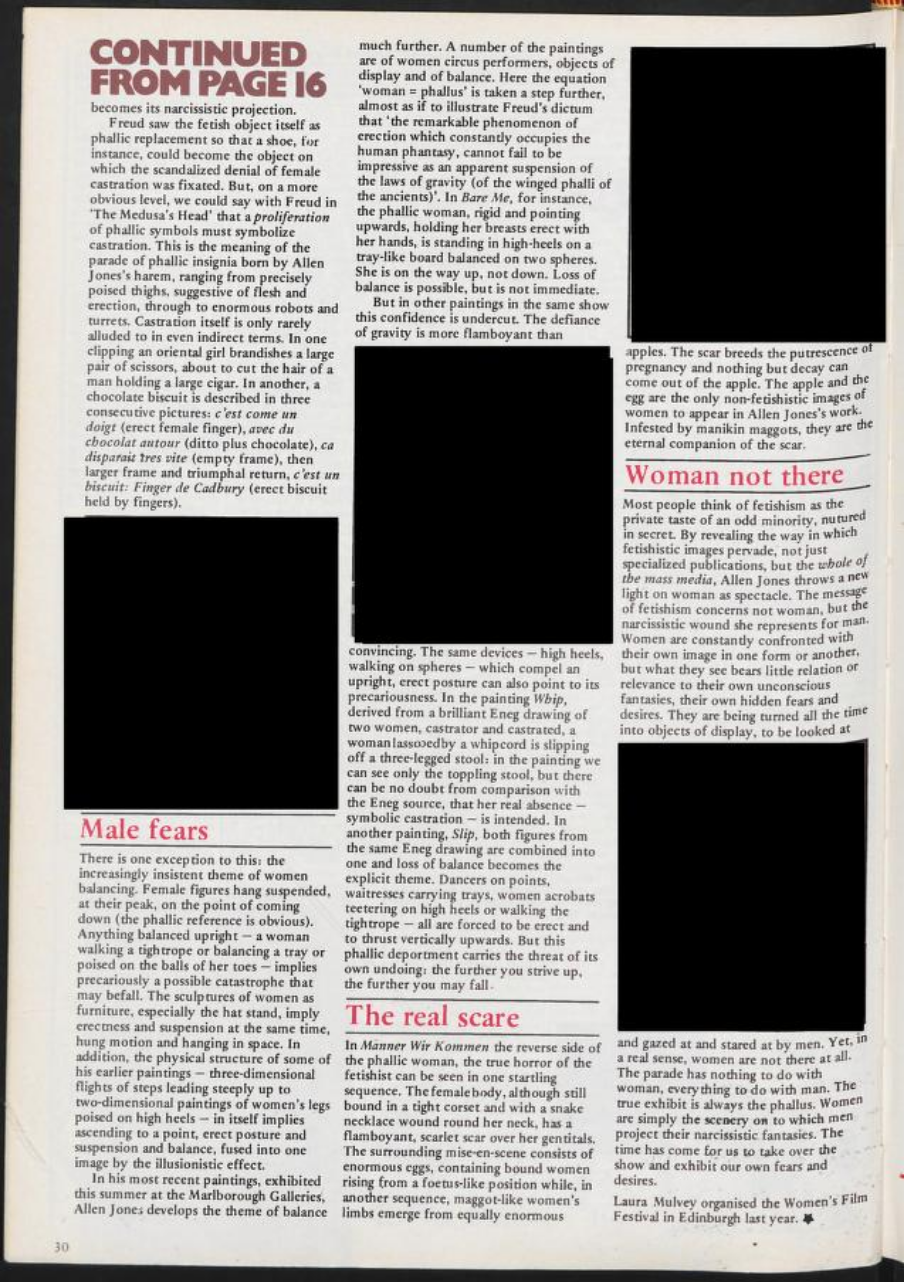

What claims to be a complete archive of Spare Rib is extant on the website, and the above issue was easy to find. So I clicked on it and I began flipping through and then I came to this page and I went, “oh”.

Like, oh oh. And it only got worse from there. Like, oh hello.

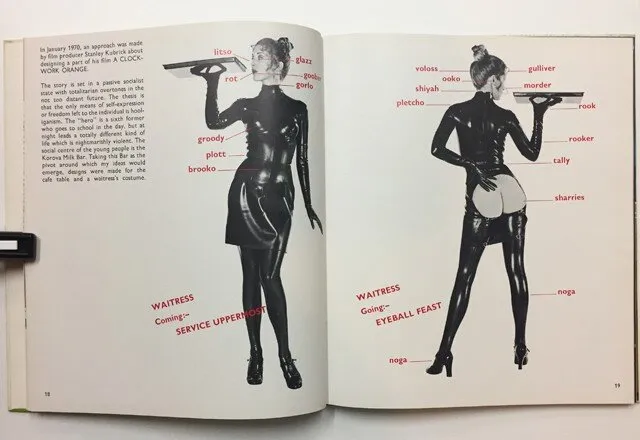

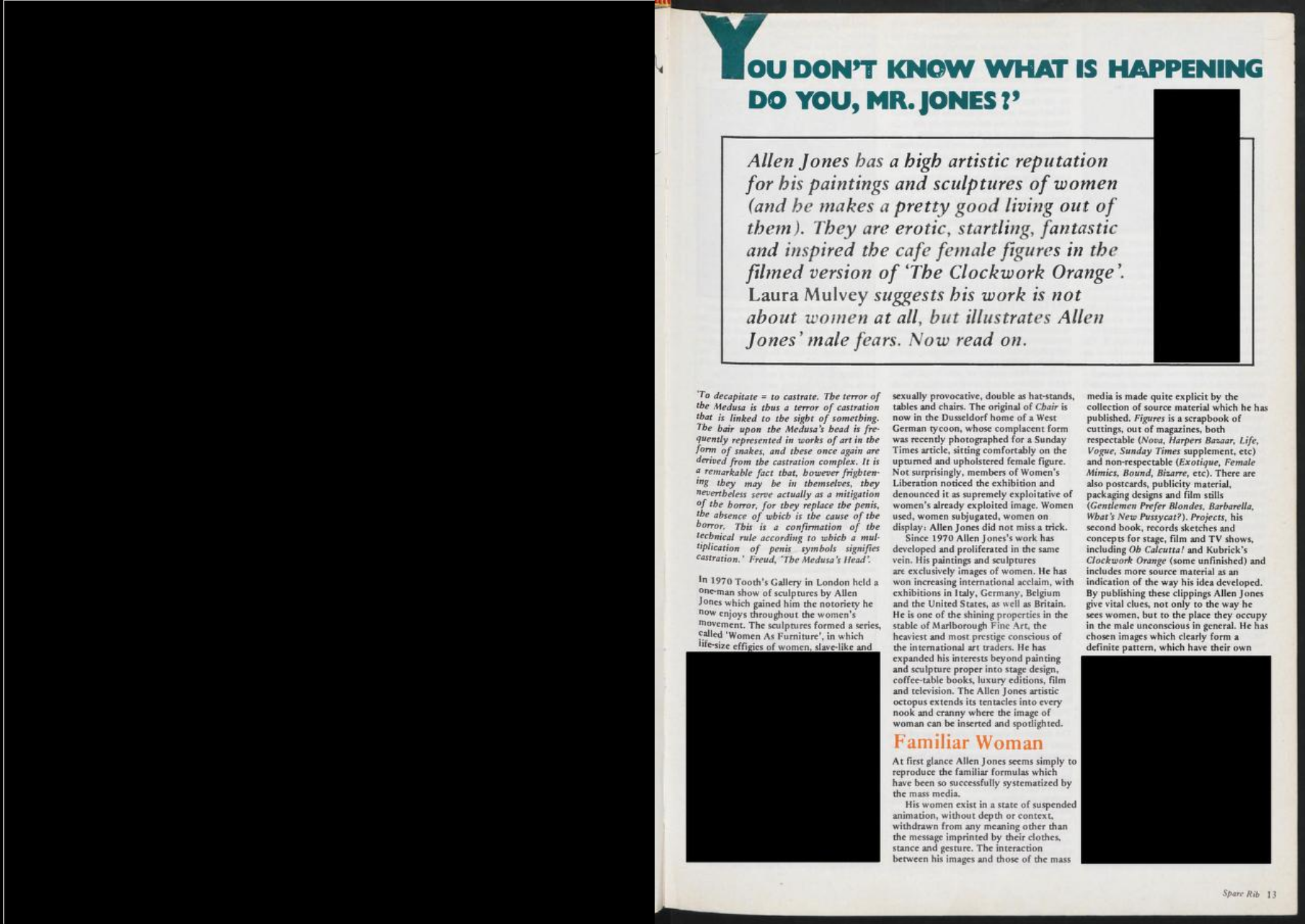

You do realize that in any way censoring an article in any way adjacent to A Clockwork Orange is a bit ironic, right? And if you’re curious about the Lillian Roxon article, it looked like this:

Well, if only I’d taken that opportunity to study a summer in Germany. Now, the back end of the scan includes a table of the usage rights to specific portions of the issue — the British Library had embarked on a public campaign to attract all of the copyright holders when they were digitizing the ‘zine to make sure everything was kosher. But these two pages are simply not listed. I could go over to ElegantlyPapered.com, the renowned dealer of vintage magazines from which the cover image is sourced from, and purchase a copy the desired issue, but that would cost me one-hundred and fifty pounds and I’m not interested in doing that for two pages that interest me.

So for now, I wait. I wait for someone to (finally) compile a comprehensive anthology of Roxon’s work and in the meantime I can read about Laura Mulvey’s problems with Allen Jones’ art but I can’t look at Jones’ art to judge if Mulvey is in the right when she accuses him of harboring castration anxiety. I can also go elsewhere on the internet and look at Chair and excerpts from Projects and read this article that mentions Mulvey’s take, as well as other instances of misguided feminist opposition to Jones’ work, in its opening paragraph before going on to defend his images as complex, playful, and utterly indisposable in the wider history of British pop art. And I can even recognize this unfortunate example of censorship as, in its own way, an accidental form of pop art itself — a visual conversation starter about what we as a culture accidentally label as potentially vulgar for reasons that have nothing to do with vulgarity. Like Beethoven, for instance.