Fisheries Issues

Fish are Mostly Gone

Most fish stocks throughout the ocean are over fished despite fisheries regulations. Over fishing has reduced the populations of fish, turtles, sharks, and whales to 0.1 – 40 percent of their values 50 to 100 or more years ago. Some popular fish, such as blue-fin tuna, are approaching extinction.

Read this very important article by Jeremy Jackson and colleagues on Historical Over fishing and the Recent Collapse of Coastal Ecosystems from Science (2001), Volume 293, pages 629 to 638, in which they show that "Historical abundances of large consumer species were fantastically large in comparison with recent observations."

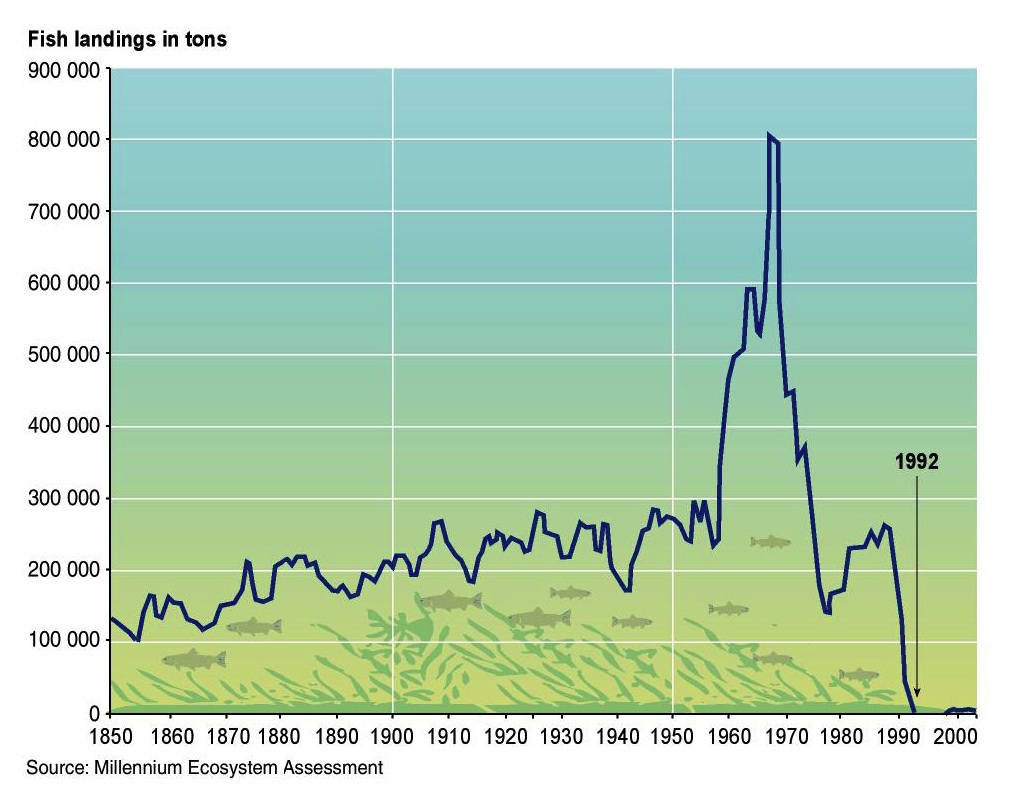

George Rose of Memorial University in Newfoundland has reconstructed the population size of cod back to 1505 when Europeans first dipped their hooks and nets in North American waters ... His best guess is that there were 7 million tonnes of cod swarming the banks and coasts of Canada in 1505, made up of several billion fish. By the time the cod moratorium was announced in 1992, there were just 22,000 tonnes left, one-third of 1 percent [0.3%] of the original population ... Andy Rosenberg and colleagues from the University of New Hampshire have taken a different approach to estimate the abundance of cod in grounds further south. They examined logbook records from the 1850s .... with 326 logbooks available for boats fishing all or part of time in the area ... Their best guess is that there were 1.26 million tonnes of cod on the shelf. The figure is in the same range as Rose's, given that the Scotian Shelf covers a smaller area and that by the 1850s, fishing had almost certainly significantly reduced the size of stocks from their pristine levels. The estimated stock size in 2002 was just 3,000 tonnes, one-third of 1 percent [0.3%] of the 1850s level.

From The Unnatural History of the Sea (2007).The estimated combined weight of the adult cod population in 1992 was a mere 1.1 percent of its historic levels of the early 1960s. In 1992 the government finally closed the Banks altogether to allow the stock to recover. But by then it was far too late. Even if left alone, the northern cod may never recover. Industrial technology and human greed may have so decimated these hardy fish that they can no longer hold onto their ecological niche. The crash could be irreversible.

From E Magazine A Run On The Banks.

Cod stocks on Canada's East Coast have failed to rebound more than a decade after the fishery was closed. Orange roughy stocks in the southwest Indian Ocean were fished to depletion in three years by 40 vessels while negotiations to create a regional fisheries management organization (RFMO) were underway. Catches by European Union (EU) countries dropped 20 per cent between 1990 and 2002.

From the Canadian governments Over fishing and Fishing Governance web site on State of the Global Fishery.The surging popularity of sushi and sashimi has devastated the bluefin tuna. Overfishing has slashed populations in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans, pushing the species toward extinction. Regulatory bodies have failed to set sufficiently strict catch quotas, and illegal fishing is rampant.

From Scientific American The Blue Fin In Peril.Today the whole bay [Chesapeake Bay] yields only 80,000 bushels a year [of oysters], down from a peak of 15 million in the nineteenth century. [Down to 0.5% of the peak].

From The Unnatural History of the Sea (2007).

Jackson (2001) estimated green turtle populations in the Caribbean Sea dropped from 33 million in the time of Columbus to1 million in 2000 [down to 3% of the peak]. He estimated that white abalone populations went from 2,000/hectare in 1970 to 1/hectare in 2000, down to 0.05% of the peak. 1 hectare = 10,000 square meters = 2.47 acres (approximately).

The decimation of fish stocks continues as seen in these plots of recent fish landings (catch) from NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service Fishwatch.

What Was It Like Before Fish Were Exploited?

It was almost like a hallucination. Immediate. A sense of dislocation. Something was awry... I had flopped overboard from a dinghy on a glassy Caribbean sea in the summer of the year 2000 and in an instant, apparently, slipped backward nearly half a century into an underwater realm that had not existed, so far as I knew, since the 1950s... Residents swarmed over me, welcoming me to the neighborhood, animals in numbers and diversity I hadn't seen in decades, not since Lyndon Johnson was president. Schools of yellowtail snappers and blue creole wrasses darted about in a frenzy. A squadron of glittering tarpon passed regally by, ... Green moray eels slid part way out of their crevice homes,...

From National Geographic: Cuba Reefs: A Last Caribbean Refuge, February 2002.When I came to Texas in 1910, I could blindfold myself, get in a rowboat with no oars–just a push pole–push my way to the fishing grounds, and catch a hundred pounds or more of trout and redfish in a few hours using a twenty-foot cane pole, line, leader, and float for tackle.

From Fishing Yesterday's Gulf Coast by Barney Farley.The abundance of sea fish are almost beyond believing. [Offshore of New England.]

Francis Higgenson in 1629, in Kurlansky, Cod, page 70

There are two versions of an unexploited fishery, the one that existed before we began fishing.

- An ecosystem dominated by great numbers of fish of all sizes, from

small fry to large, top predators. This is the traditional pyramid

with many small fish, fewer mid-sized fish, and still fewer top predators.

Large numbers of fish at Palmyra Island, an un-exploited ecosystem in the Pacific. The photo shows a school of convict surgeonfish swimming around dead coral off Palmyra Atoll. The plant-eating fish are known for keeping algae in check in coral reef ecosystems. This is the common view of a tropical paradise.

From Explorations: Magazine of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Paradise Redefined.

- An ecosystem dominated by top predators with very few other fish.

This is the inverted pyramid recently discovered by Scripps scientists

in remote coral islands in the Pacific.

The inverted pyramid ecosystem, dominated by top predators, a gray reef shark in this photo, and very few other fish. The photo was taken at Kingman Reef, an uninhabited, virtually undisturbed ecosystem. This too is a tropical paradise, but not one that was expected.

From Explorations: Magazine of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Paradise Redefined.

How Important Are Fisheries to the Economy of Any Region?

Fisheries are not very valuable. For the entire United States, the total value of fish landed was only about 4% of the total value of livestock and poultry raised on land. For Texas, the total value of fish landed was $0.19B in 1999 according to the Texas Almanac (page 124) while total cash receipts for livestock and products was $8.4B in 1999 (same, page 603). Thus for Texas the value of fish from the ocean was about 2.3% of the value of livestock from land.

In 2006, the total weight of all fish caught in US waters was 4,308,523 metric tons, worth $4.0 billion dollars. In Texas, the values were 53,130 metric tons worth $0.2 billion dollars. The NOAA Fisheries Statistics Division of the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) has automated data summary programs that anyone can use to rapidly and easily summarize U.S. commercial fisheries landings.

Recreational fisheries are far more important. Recreational fishers caught 100,925 metric tons of fish in 2006. While this is only 2.3% of the commercial harvest, the large number of fishers, their use of hotels and restaurants in coastal areas, and their purchase of gear, make important contributions to the coastal economy. 13 million saltwater fishers made 89 million fishing trips and caught 475 million fish in 2006.

Every year, more than 12 million Americans enjoy wetting a line in our oceans and along our coasts. More than just a traditional American pastime and contributor to conservation, saltwater recreational fishing is a major economic driver generating more than $30 billion in economic impact and supporting nearly 350,000 jobs nationwide.

From National Marine Fisheries Service.

How Many Can Now Be Caught?

The basic question is: How many fish can be harvested from the sea? The answer is not simple. Some fish stocks are declining. Is the decline due to over fishing? Is it due indirectly to fishing for other types of fish? Or is it due to the natural variability of the stock? If it is due to over fishing, what can be done? Reduce the number of ships? Limit the fishing season?

Because the answers are somewhat fuzzy, fishery regulatory bodies always err on the side of over fishing. In most instances, the regulatory bodies have ignored scientific advice.

Who Regulates Fishing?

In the United States, states regulate fishing from the coast out to 3 nautical miles, except Texas and West Florida, who regulate fishing to 9 nautical miles. The federal government regulates fishing from 3 nautical (or 9 nautical miles) to the outer limit of the Exclusive Economic Zone, 200 nautical miles. See the web page on the Coastal Zone.

Unfortunately, no one is in charge.

Over 20 federal agencies operating under dozens of laws regulate activities, support ocean-based commerce, and protect marine species and habitats in the territorial sea and EEZ. These agencies separately manage parts of marine ecosystems, without any systematic effort to coordinate their actions for the public good.

From Turnipseed et al (2009).

A cacophony of activities, most regulated by separate federal agencies, crowd ocean waters in the Gulf of Maine. A federal public trust doctrine extended to all U.S. ocean waters would identify these agencies as trustees of the U.S. ocean public trust, unifying them for the first time under a common mandate to manage marine resources sustainably. LNG, liquified natural gas; OPAREAs, Operating areas.

From Turnipseed et al (2009).

In international waters, beyond 200 nautical miles, some fisheries are regulated by international treaty organizations such as the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas, which has attempted, with little success, to regulate the bluefin tuna catch in the Atlantic and Mediterranean. The Inter American Tropical Tuna Commission has been almost as unsuccessful regulating tuna fishing in the eastern Pacific, from the American coast to 150°W and from 50°S to 50°N.

Unfortunately, illegal fishing is very common, and many fish stocks are not regulated.

On a standard 5-7 week fishing trip these poachers might expect to take anything from 500 to 800 tonnes . You're talking about several million dollars worth of fish for a month's fishing, which means that you can pay off a boat in a week or two.

From Television Trust for the Environment Earth Report.

The rogue fishing vessel Viarsa 1 fleeing the Australian Fisheries and Customs patrol vessel Southern Supporter after it was found fishing illegally in Australia's sub-Antarctic waters. The ship was captured after a 20-day chase through high seas as the ship tried to return at maximum speed to Uruguay. The chase was documented in the best-selling book Hooked: Pirates, Poaching and the Perfect Fish by Bruce Knecht.

Photo from Coalition of Legal Toothfish Operators.Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, and its adverse impacts on national and regional efforts to manage fisheries in a long-term sustainable manner, is one of the main problems facing capture fisheries.

From State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2006, Food and Agriculture Organization FAO.

References

Benchley, P. (2002). Cuba reefs: a last Caribbean refuge. National Geographic Magazine. 201: 44–65.

Jackson, J. B. C., M. X. Kirby, et al. (2001). Historical Overfishing and the Recent Collapse of Coastal Ecosystems. Science 293 (5530): 629–637.

Kurlansky, M. (1997). Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World. New York, Penguin Books.

Turnipseed, M., L. B. Crowder, et al. (2009). OCEANS: Legal Bedrock for Rebuilding America's Ocean Ecosystems. Science 324 (5924): 183–184.

Revised on: 27 May, 2017

-f1.gif)