Fisheries Policy Issues

Why Are Fish Gone?

Here are some factors that

have led to the decline of fisheries in many areas of the world, as outlined

in Empty

Oceans, Empty Nets, written by Habitat

Media. The Monterey Bay Aquarium has similar information on Fisheries

Issues and Overfishing.

The problems include soaring demand, improved technology, government subsidies, poor regulations, reduced fish stocks, bycatch, and destruction of bottom organisms and habitat by bottom trawling. Essentially, fish have nowhere to hide.

Population Pressure

Fish provide a vital source of food for hundreds of millions of people worldwide. Overall, the marine catch accounts for 16% of global animal protein consumption. In general people in developing countries rely on fish as a part of their daily diets much more heavily than those residing in developed countries. For example, fish accounts for roughly 29% of the total animal protein in the diet of Asian populations, but only 7% for North Americans.

The use of fish as a source of food rose from 40 million tons in 1970 to 72 million tons in 1993. Population is by far the most important factor in this burgeoning demand, accounting for roughly two thirds of change in total demand. At current rates of world population growth, the total world supply of food fish (marine, freshwater, and aquaculture) would have to grow from roughly 72 million tons in 1993 to 91 million tons by 2010 to maintain today's per capita fish supplies, according to FAO.

From: American Association for the Advancement of Science: Marine Fisheries, Population and Consumption: Science and Policy Issues.

Factory Trawlers

To meet the demand for more fish, the fishing industry has turned to larger, more efficient ships, the most important being the factory trawlers and ships.

Vladivostok-registered Kapitan Nazin, [is] one of the largest factory trawlers in the world. The Russian ship is one of three identical craft - each 347 feet (105 m) long and 10,000-tons displacement - built in Spain in 1993. They are classified by Det Norske Veritas (DNV) to withstand ice to Class 1B and operate year-round off the Siberian coast in the Sea of Okhotsk. The Kapitan Nazin and its 165 crew can process 125 tons of frozen product per day and store up to 3,200 tons in its refrigerated hold before off-loading at sea to a freighter.

[Thousands of such trawlers are fishing at sea, but not as many as conventional trawlers.]

From Cascade General, Portland Shipyard press release from 1999.

But what the factory trawlers lack in numbers they more than made up for in catching power. So awesome was this power in the early years of their prime (and so good was the fishing) [about 1965-70] that it is perhaps best describes by hypothetical analogy to dry land. First, assume a vast continental forest, free for the cutting or only ineffectively guarded. Then try to imagine a mobile and completely self contained timber-cutting machine that could smash through the roughest trails of the forest, cut down the trees, mill them, and deliver consumer-ready lumber in half the time of normal logging and milling operations. This was exactly what factory trawlers did – this was exactly their effect on fish – in the forests of the deep.

From William W. Warner, 1983, Distant Water, The Fate of the North Atlantic Fisherman, page viii.

The largest factory trawler is the $65 million American Monarch, 340 feet long and displacing 6,730 tons. It can net and process about one million pounds (500 tons) of fish per day.

F/V ALASKA OCEAN. The GPA designed conversion of the 376’ Alaska Ocean, the largest US flagged factory trawler in the fleet, was completed by Ulstein Hatloe AS, Norway, for Alaska Ocean Seafood LP.

From Guido Perla & Associates.

Improved Technology

The most important improvement was the invention of frozen foods by the inventor and fisherman Clarence Birdseye. The invention enabled the distant water fisheries by factory trawlers. Trawlers freeze fish at sea, and they can travel for many months away from their home port. Trawlers from any country can fish anywhere in the world. Before the invention of frozen food, fish could be preserved only three ways:

- Air drying or smoking. Fish were taken ashore, filleted, and dried or smoked on racks. This takes months of work, and limits the amount of fish that can be preserved.

- Salting. "Salt preserves fish by removing water from the flesh and tying up the remaining water so that spoilage organisms cannot use it for growth. If enough salt is used, the fish may keep for as long as a year in a cool, dry place. Salting is one way to store fish until you are ready to smoke or pickle them." From Michigan State University Extension.

- Preserving

on ice. Fish are caught and placed on ice in the hold.

Because cod kept at 0°C, the melting point of ice, will be

virtually uneatable after fifteen days, this greatly limited the

distance fishing boats could travel, catch fish, return, and get

the fish to market. Trawlers could fish in waters only a week away

from their home port, a distance of about 1500 nautical

miles.

Left: Clarence Birdseye in his office. From Birds Eye Foods. Right: Frozen fish fillets. From BlueWater Seafoods, Quebec, Canada.

Bycatch

Although commercial fishing fleets target only a few valuable species of fish, they kill and waste billions of pounds of unmarketable marine species each year. When the catch is hauled aboard, the non-commercial marine life–“bycatch”– is separated

out and thrown back into the ocean dead. Bycatch can be fish with no commercial value, juveniles of marketable species, sea turtles and birds, marine mammals such as seals, dolphins and whales, and many other forms of ocean life.

- According to a United Nations report, commercial fisheries discard an average of 54 billion pounds of fish bycatch each year [about 27 million metric tons].

- As many as 40,000 sea turtles and more than 200,000 albatross are caught each year on longlines.

- In 2000, over 200 billion pounds of marine life were brought to market for food. Estimated bycatch equaled 21% of the total catch.

- Globally, shrimp trawlers catch approximately 22 billion pounds of bycatch each year – almost half of all bycatch.

- Long line fishing fleets, towing miles of cable strung with thousands of baited hooks intended for tuna, swordfish, and Patagonian toothfish (Chilean Sea Bass), kill tens of thousands of albatross each year, which get caught on hooks as they dive for bait.

- In 1992 the Alaska fishing fleet threw back 442 million pounds of bycatch, almost twice the amount of fish landed by the entire domestic fishing effort in New England that year.

- For every pound of shrimp caught in the Gulf of Mexico, between four and eight pounds of marine bycatch is discarded.

- For finfish, the ratio of bycatch to target fish can be as high as 11:1 because the bycatch is either too young, out of season, or the vessel has no permit to keep it. In 1998, U.S. pelagic Atlantic longlines fishing discarded 22,536 sword fish, 1,274 blue marlin, 1,485 white marlin, and 1,304 bluefin tuna as bycatch."

From: Conserve Our Ocean Legacy.

Pollution and Habitat Loss

- Coastal Pollution.

Coastal waters provide critical spawning, nursery or other habitat for many commercially important marine fish populations. These waters are under a multitude of assaults that stem principally from human activities on land. For example, roughly 80% of marine pollution is estimated to come from land based sources. Development along the coast has destroyed an estimated 50% of all coastal wetlands worldwide."

From: American Association for the Advancement of Science: Marine Fisheries, Population and Consumption: Science and Policy Issues.

- Trawling and Dredging for Fish.

The National Academy report on Effects of Trawling and Dredging on Sea-floor Habitat notes:- A single passage of a scallop dredge can destroy or damage living maerl, plants, and animals to a depth of 10 cm, and the track remains visible for 2.5 years.

- Trawled sea floor areas have a 75 % reduction in total productivity.

- In the Gulf of Mexico, bottom trawling for shrimp scours 255% of the sea floor each year. This means that every square meter of sea floor out to depths of 90 meters is trawled 2.5 times a year on average.

Many studies report that repeated trawling and dredging causes a shift from communities dominated by species with relatively large adult body size toward dominance by high abundances of small-bodied organisms. Intensively fished areas are likely to remain permanently altered, inhabited by fauna that readapted to frequent physical disturbance. Specie richness (the number of species per unit area) and evenness (the relative abundance of resident species) – two measures of species diversity – can decline in response to bottom fishing..." The percentage of area trawled off New England exceeded 307%, that is, each square meter of the sea floor was trawled or dredged more than three times each year (Figure B2 of the report).

A new study by the National Academy of Sciences [Effects of Trawling and Dredging on Seafloor Habitat] released today says that bottom trawling, a method of fishing that drags big, heavy nets across the sea floor, is killing vast numbers of marine animals. Coming after years of declining U.S. fisheries, the report finds that bottom trawling damages the habitat where juvenile fishes hide from their predators, and can significantly alter the marine ecosystem.

From Effects of Trawling and Dredging on Seafloor Habitat. Committee on Ecosystem Effects of Fishing. National Academy Press, 2002.

i1.0.jpg)

Shrimp trawlers (see inset) off the coast of China. The long plumes of sediment churned up by their nets — 'mud trails' — are a highly visible sign of the disturbance to sea-bottom ecosystems that they leave in their wake.

From Anonymous (2007). "Snapshot: Ghosts of destruction." Nature 447(7141): 123-123.

Government Policy

- Subsidies for fishing industry.

Government subsidies have lead to overcapacity in all important fishing areas. At its core, the crisis in over fishing stems from the fact that the world now has a substantial overabundance of fishing capacity. Industrialized fleets aided by sonar, sophisticated satellite technology and highly efficient gear are now capable of fishing out vast areas of the ocean in very short order. The predictable results of overcapitalized fleets have been over fishing and depletion of stocks as well as substantial economic losses. FAO estimates that to rehabilitate fisheries to 1970 abundance levels and catch rates would require the removal of 23% of the existing gross weight tonnage of the world's fleet.

Governments worldwide, anxious to preserve employment in fishing and shipbuilding and ameliorate the economic disruption caused by over fishing, have subsidized economic losses in the fisheries sector to the tune of $54 billion a year, according to FAO. Such subsidies serve to perpetuate over fishing and economic distress in the fishing sector.

From American Association for the Advancement of Science: Marine Fisheries, Population and Consumption: Science and Policy Issues

- Failure of Fisheries Scientists to Provide

Accurate Advice. Ransom

Aldrich Myers (1952–2007) was one of the first to notice

that over fishing of cod offshore of Newfoundland, Canada, not

the voracious seals, cold temperatures and other excuses invented by an agency that, by caving in to industry pressure, had failed to protect this vital resource and the province that depended on it. He was a leader among the handful of Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) scientists who published evidence that excessive fishing was the sole cause of the stock's collapse.

Unsurprisingly, given the press and public reaction to these papers, Myers was reprimanded by his superiors. He took refuge in academia, taking in 1997 the Killam Chair in Ocean Studies at Dalhousie [university]. From there, aided by colleagues and several brilliant graduate students, he published a series of papers showing that politically motivated, slothful optimism had masked the systematic destruction of marine resources, and marine biodiversity in general — not just in Canada and its marine jurisdictions, but the world over.

These papers, again based on judicious analysis of existing time-series data, documented the worldwide depletion, through industrial fishing, of skate, sharks, large bottom fishes and, finally, large pelagic fishes such as marlin and tuna. Each new paper baited the staff of yet another agency into angry rebuttals. Myers had the thick skin required for such acrimonious debates. Once, when asked about the controversy that one of his papers had generated, his response was simply: "They are wrong, and I am right!"

In the process, Myers helped to found fisheries conservation biology. This discipline is devoted to identifying exploited fish populations and species threatened with extinction, and suggesting measures for rebuilding them, along with the ecosystems in which they are embedded. Correspondingly, its primary clients are not the owners of trawlers, longliners, purse seiners and other industrial vessels, but national and international agencies mandated with maintaining marine biodiversity and ecosystems, and the many benefits they provide for society as a whole.

From Pauly (2007). Obituary: Ransom Aldrich Myers (1952-2007). Nature 447 (7141): 160-160.

-i1.0.jpg)

Ransom Aldrich Myers, fisheries scientist who dared to be right.

- Failure to regulate fishing.

In principle, fish are protected everywhere:

Freedom of the high seas" is a principle considered by a few to mean that the high seas are res nullius or "without law" and beyond the jurisdiction of any nation State except that of the flag state. Res nullius is an antiquated concept. In fact, customary and conventional international law indicate that the high seas and its resources are subject to res communis or the "law of the commons". Numerous treaties, including the United Nations Law of the Sea Convention (UNCLOS), restrict the use of the global ocean commons to that which is "reasonable" and does not infringe on the rights of others. "Freedom of fishing" for example, is subject to a whole host of conditions, indicative that the world community considers high seas fishing resources to be common property resources.

From International Law Governing Driftnet Fishing On the High Seas, Earthtrust.

In practice, the history of fishing regulations is mostly a history of failure. Governments cannot agree on sustainable levels of fishing, leading to over fishing in almost all areas. Fish in many areas beyond the 200 mile Exclusive Economic Zones of coastal countries often have little protection despite the UN Convention on Fishing and Conservation of the Living Resources of the High Seas (1958).

Fishing ships move to countries that do not enforce the international treaties. Or countries ignore international law. For example

Despite the 1989 UN driftnet resolution (44/225) prohibiting further expansion of driftnet fishing it was reported that Taiwan expanded its operations in the Atlantic Ocean and that France increased its fleet from 37 driftnet vessels in 1989 to 78 vessels in 1991 in the Northeast Atlantic.

From Earthtrust.

Alaska does a better job of regulating fisheries than does Texas. Every body of water in Alaska has its own regulations.

My guess is that when you live in a climate as severe as coastal Alaska, you develop an extra-sensory consciousness of the environment. You cannot help but notice the entire balance of nature sagging under the weight of man. It's almost as if the general population embraces rather than challenges the regulations Fish and Game have designed for conservation of resources.

— Everett Johnson, Texas Salt Water Fishing, October 2006, page 5.

Solutions

- Set up marine protected areas.

- New Zealand closed to bottom trawl fishing methods, including dredging seven Benthic Protection Areas within their Exclusive Economic Zone. The area comprises more than 1.2 million square kilometers of seabed. The area is 32% of the seabed in their exclusive economic zone, 52% of their seamounts, and 88% of their hydrothermal vents. Fishing within 50 meters is deemed to be touching the seabed and is a serious criminal offence, and will attract a fine of $100,000 and the vessel will be seized.

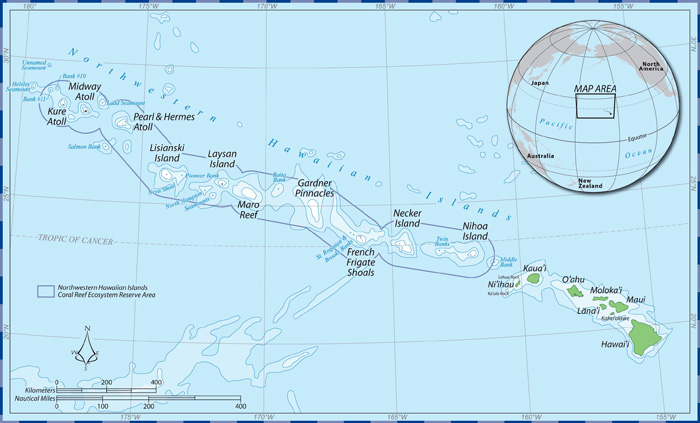

- The United States created the largest fully protected ocean conservation

area in the world, the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument

in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

Northwest Hawaiian Islands Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument.

From NOAA Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument.

- California has set aside 203 square miles of Marine Protected Areas along the California coast. Of these, 85 square miles are Marine Protected Reserves that are are no take zones in which some commercial and recreational fishing is prohibited. Unfortunately, most allow recreational taking of many species of fish, and shell fish, including red abalone, chiones, clams, cockles, rock scallops, native oysters, crabs, lobster, ghost shrimp, sea urchins, mussels, and marine worm and finfish. The Marine Protected Reserves are relatively small, extending about five nautical miles along the coast and out three nautical miles. The limits are lines of latitude and longitude, allowing easy determination by fishers and enforcements agencies. The California Department of Fish and Game has a brochure listing the areas.

- Hawaii has set aside a few small Marine

Life Conservation Districts where most or all marine life is protected.

- Reduce coastal development and protect lagoons and estuaries, the

nurseries of many marine species. The pages on Coastal

Pollution Policy Issues outlines ways these areas are being protected.

- Reduce the number of fishing licenses. The State of Texas has been

buying back thousands of shrimp fishing licenses to reduce the number

of boats trawling for shrimp. "Texas Parks and Wildlife Department

has retired 1,187 of 3,231 licenses on the books at a cost of $7.2

million. The overall number of inshore shrimp vessels in Texas waters

has decreased from around 2,100 down to around 1,200 since the buyback

program began." TDPW.

By 2007 less than 700 shrimping vessels are still eligible for shrimping

activity, and only 138 were active on the first day of the shrimping

season, down from 886 shrimping vessels active on the day of the shrimping

season in 1995–Houston

Chronicle.

- Require Turtle Excluding Devices and Bycatch Reduction Devices on

trawls. This reduces the by catch of turtles and other larger marine

animals from shrimp trawls. The Bycatch Reduction Devices mus reduce

bycatch of fin fish by 30%.

- Think locally, don't eat endangered fish. Which fish should we

eat, which should we avoid because they are over fished or because

fishing harms the environment? See the Monterey Bay Aquarium's Seafood

Watch, their list

of fish to eat or not eat, and their pocket

guides.

- The Marine Stewardship Council certifies fisheries that meet their standards for stainable harvests. Their label can be found on seafood in markets, especially in Europe.

Revised on: 27 May, 2017